Cloud Firestore is Google’s premier NoSQL document-oriented database, it sports:

“automatic multi-region data replication, strong consistency guarantees, atomic batch operations, and real transaction support. We've designed Cloud Firestore to handle the toughest database workloads from the world's biggest apps” src

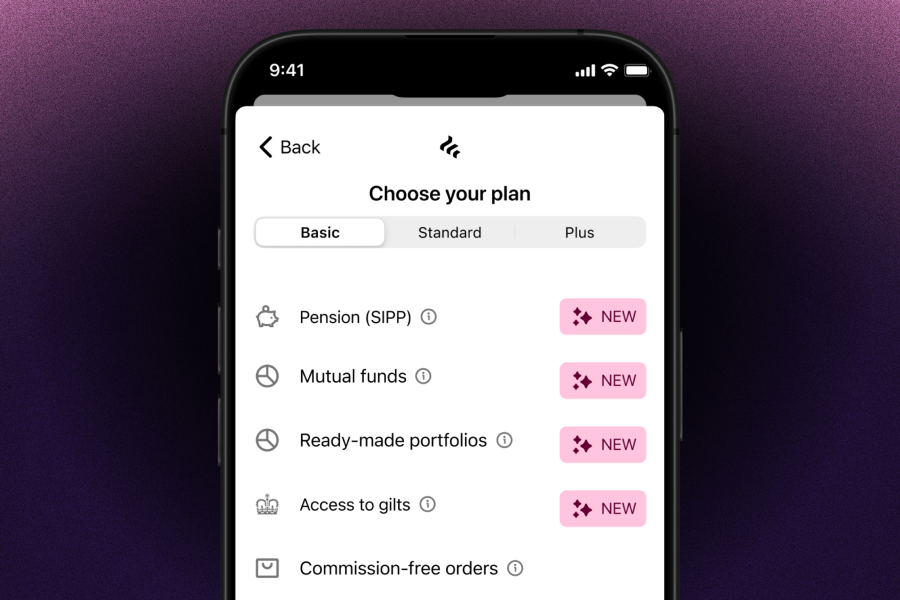

At Freetrade we get an enormous amount of value from this robust, autoscaling database.

Particular points of note:

- It has enough transactional support to ensure data consistency, whilst also reaping the benefits of an auto-scaling NoSQL store

- Data changes can trigger cloud functions, allowing us to build event-based flows

- Mobile SDKs for Android and iOS, allowing our apps to subscribe directly to changes in the database and respond immediately

For all our love of Firestore, it does come with its challenges, many of which relate to the import/export tool. Below are a collection of lessons learnt on the road to productionising our use of Firestore.

Lesson 1: Make sure your collection IDs are unique, even sub-collections

Firestore paths are made up of an alternating sequence of collection and document ids:

/<COLLECTION_ID>/<DOCUMENT_ID>/<COLLECTION_ID>…

It is very easy to make the mistake of thinking that the lower level collection IDs are “fully qualified” and isolated from others of the same name, but that’s not how it works.

Take, for example, the following example data structures:

/snapshots/<ID>/history

/prices/<ID>/history

Here we have two history collections, with very different purposes and containing very different data.

At first look this structure seems reasonable and the basics work fine, if you query /snapshots/<ID>/history you only get back snapshot documents, if you query /prices/<ID>/history you only get price documents.

Makes sense, the two are totally separate, right? Wrong!

Under the hood in Firestore, these two history collections are actually one and the same. This can lead to a number of unexpected issues, for example:

- Index rules and exceptions are set per collection ID, so if you have a specific index-exemption optimisation you want to apply, or a potentially expensive compound index you want to create, you can’t create it for just one usage of the history collection ID. It will be applied to all, not necessarily what you want

- You can’t use the Firestore import/export tool on a fully qualified path, you can only use it on specific collection IDs. So it is impossible to backup or restore the /snapshots/<ID>/history or /prices/<ID>/history documents in isolation, you have to mix what might be very different types of data

- The Firestore import/export tool assumes that the data for a given collection ID is homogeneous. This is an undocumented assumption. So in our example, if the /snapshots/<ID>/history collection has a small number of large documents and the /prices/<ID>/history collection has a very large number of small documents, that means bad times for whatever internal partitioning the import/export tool is using. We have personally experienced import/export times jumping from minutes to several hours, due to storing non-homogeneous data. This is a very easy mistake to make when seemingly separate collections are actually linked

The solution for all of this is simple, albeit ugly and against my preference for DRY. Your collection IDs should avoid generic names and instead should be unique per use case, like this:

/snapshots/<ID>/snapshots_history

/prices/<ID>/prices_history

Lesson 2: Delete or archive old Firestore documents

Firestore does not provide any kind of automated backup service. The closest thing they have is the import/export tool, which you have to orchestrate yourself.

This tool allows you to take a backup of the database relatively easily, however it is important to realise that it is not a delta, it is a full backup of every document in the database and you are billed for the cost of a read on every one of those documents!

At first look, the costs of Firestore look pretty affordable (and they are) with read costs a tiny $0.036/100k document reads. As your database size increases though, these costs really start to stack up.

Costs per backup (assuming 1 backup per day):

10M doc backup -> $3.6/day -> $109.20/month

100M doc backup -> $36/day -> $1092/month

500M doc backup -> $180/day -> $5460/month

If, like us, your risk tolerance means you need to backup your data multiple times per day and regulations mean you need to retain data for years, then the multiples can quickly make the cost of keeping everything in Firestore unsustainable, especially if your data design is biased towards lots of small documents.

As a result of the above I would strongly recommend you consider what data you need to hold onto and what you can delete outright. For historical data that needs to be retained, consider developing an archival process where you move documents to a cheaper long-term storage medium.

It has taken non-trivial effort, but by keeping our Firestore dataset to a lean record of current data, we have kept the costs very reasonable. In future we may look at rolling our own streaming backup utility, but I really hope that Google comes up with a managed service before we resort to that.

Lesson 3: Don’t use dynamic collection IDs

Some of our initial data structures involved dynamically created collection IDs. On the face of it this seemed a perfectly reasonable design decision, for example partitioning data by date:

/prices/<ID>/2020-01-01/...

/prices/<ID>/2020-01-02/…

In this example 2020-01-01 and 2020-01-02 are distinct collection IDs, with collections of documents that sit underneath them.

This approach works seamlessly and Firestore allows you to implicitly declare collections just by creating the documents underneath them, something Google themselves highlight.

The devil however, is in the detail. While this kind of structure might seem perfectly functional when you first start using it, there are problems:

- Custom indexes and exemptions have to be created per collection ID and there are some quite low limits on the numbers of those you can create

- The Firestore import/export tool can’t handle databases with high hundreds or thousands of collection IDs. We saw our export/import times jump from from minutes to several hours because we crossed some some threshold, internal to the workings of their tool

We recommend you avoid any kind of dynamic collection naming and keep the number of unique collections to the 10s or low hundreds. In some cases this has meant we’ve needed to introduce superfluous intermediate collection/documents to avoid the dynamic collection IDs. For example, the following structure shifts the dynamic date ID to be on a document ID, rather than a collection ID.

/prices/<ID>/prices_by_date/2020-01-01/price_items/…

/prices/<ID>/prices_by_date/2020-01-02/price_items/…

Ugly but effective.

You absolutely wouldn’t do this intuitively unless you knew about the issues related to dynamic collection IDs.

Lesson 4: Manage your own “missing documents”

Firestore paths are made up of an alternating sequence of collection and document IDs:

/<COLLECTION_ID>/<DOCUMENT_ID>/<COLLECTION_ID>…

But it is entirely possible and valid that your path might have “missing” documents at the intermediate levels. For example, our event-sourcing data structure looks something like this:

/clients/<CLIENT_ID>/events/<EVENT_ID>

In this example /clients/<CLIENT_ID> is a document that doesn’t actually exist, it is just an intermediate part of the path used to partition the events by client.

This structure works fine when you’re directly addressing an individual client, but is problematic when you want to enumerate all clients.

Regular collection queries do not include “missing” documents - the only way the SDK gives you to list them is a dedicated listDocuments method.

A key detail about listDocuments is that it does not give you any hooks for pagination, it simply returns all documents. This clearly won’t scale forever and indeed we saw this method starting to fail once our collections got into the 10ks of documents.

This is more dangerous than it might seem at first. If your document IDs aren’t predictable, a UUID for example, then you could very easily be left with data in your database that you can’t find.

As a result of the above, we recommend either designing a data structure that doesn’t involve “missing” documents, or maintaining a separate collection of concrete documents that you can paginate through.

Conclusion

As mentioned at the outset, we at Freetrade get an enormous amount of value from Firestore, there is so much power that it provides out-of-the-box.

As we’ve listed however, there are a bunch of gotchas that are not readily apparent when you first start out with the database. Hopefully you can save yourself some pain by learning from our mistakes.