Pound-cost averaging and lump sum investing are two different investment strategies, and either could be the tonic for your stock market timing stresses.

In short, pound-cost averaging involves regular and consistent contributions, while lump sum investing is the exact opposite, as it sees you invest a large chunk of money all at once.

But let’s examine the nuances of the two, find out more about how and when they might work, and ultimately help you to decide when to invest a lump sum and when to drip-feed into investments.

What is pound-cost averaging?

Pound-cost averaging, synonymous with dollar-cost averaging, is a regular investing strategy investors often use to smooth out the ups and downs of the market.

It involves investing the same, or roughly the same, amount of money at regular intervals. This will result in the purchase of more individual units of an asset when prices are low and fewer units when prices are high.

The goal is to end up with an average purchase price which should look a lot smoother throughout the life of the investment.

How does pound-cost averaging work?

Theory is great, but let's look at how pound-cost averaging works in practice. In basic terms, you need to:

- Pick an investment

- Choose the regular interval at which you will invest

- Decide how much to regularly invest

- Stick to the plan.

You can even use recurring orders to automate this process.

So, let’s look at an example which can showcase the potential benefits of pound-cost averaging.

Pound-cost averaging example

The same 245 shares would have cost £2,450 at the time of the first investment. In this example, drip feeding money into the market at monthly intervals resulted in a lower cost than a single lump sum investment.

But this is not always the case. Things could have gone the other way.

If the shares had instead climbed on a consistent basis over the year, you may have been better off buying them all at once initially.

While pound-cost investing smooths out any declines in the market value of an investment, it also smooths out any big gains, meaning you may not generate as big a return had you invested a lump sum upfront.

And there could have been a dividend on offer at some stage during the year, which would have benefited from an initial lump sum investment too.

The key here is that we just don't know how the market or a specific stock will look in a given period of time. So, as we've said, there's a psychological benefit to investing regularly and knowing all of your money isn't exposed to any potential drops.

In short, pound-cost averaging is about:

- Investing in a way that's practical and fits in with when you get paid.

- Not having to guess or get sucked into market timing.

- Making those ups and downs look a whole lot smoother over the long term.

What is lump sum investing?

Unlike pound cost averaging, lump sum investing puts your money to work straight away. Given we know the time you give your money to grow is an incredibly important aspect of long-term investing, putting that lump sum into the market right away rather than spacing out regular investments certainly can have some benefits.

Lump sum investing can make sense where an investment platform has high trading fees, too. If you have to pay £10 every time you buy a stock, investment trust or exchange-traded fund (ETF), that would already set you back £120 a year on a monthly investing plan. So, it's probably more reasonable for investors to save up two or three months' worth of earmarked money and invest that less frequently.

It would be disappointing to let the platform dictate your strategy, though, especially if it leads to an erratic investment schedule just because of pricing outside your control.

That's much less of a consideration when those trading costs are low or the platform is commission-free.

There's a behavioural niggle that can crop up if you're storing up a few months' worth of cash as well, and that's the urge to want to time the market. We’ve seen how difficult that can be!

What is timing the market?

Whether you're sitting with a lump sum from an inheritance, a bonus, or just general under-the-bed savings that you'd like to invest, there is always the temptation to hold off for a slightly better price tomorrow.

This concern about timing the market might have you stuck between investing a lump sum, using pound-cost averaging, or some other technique.

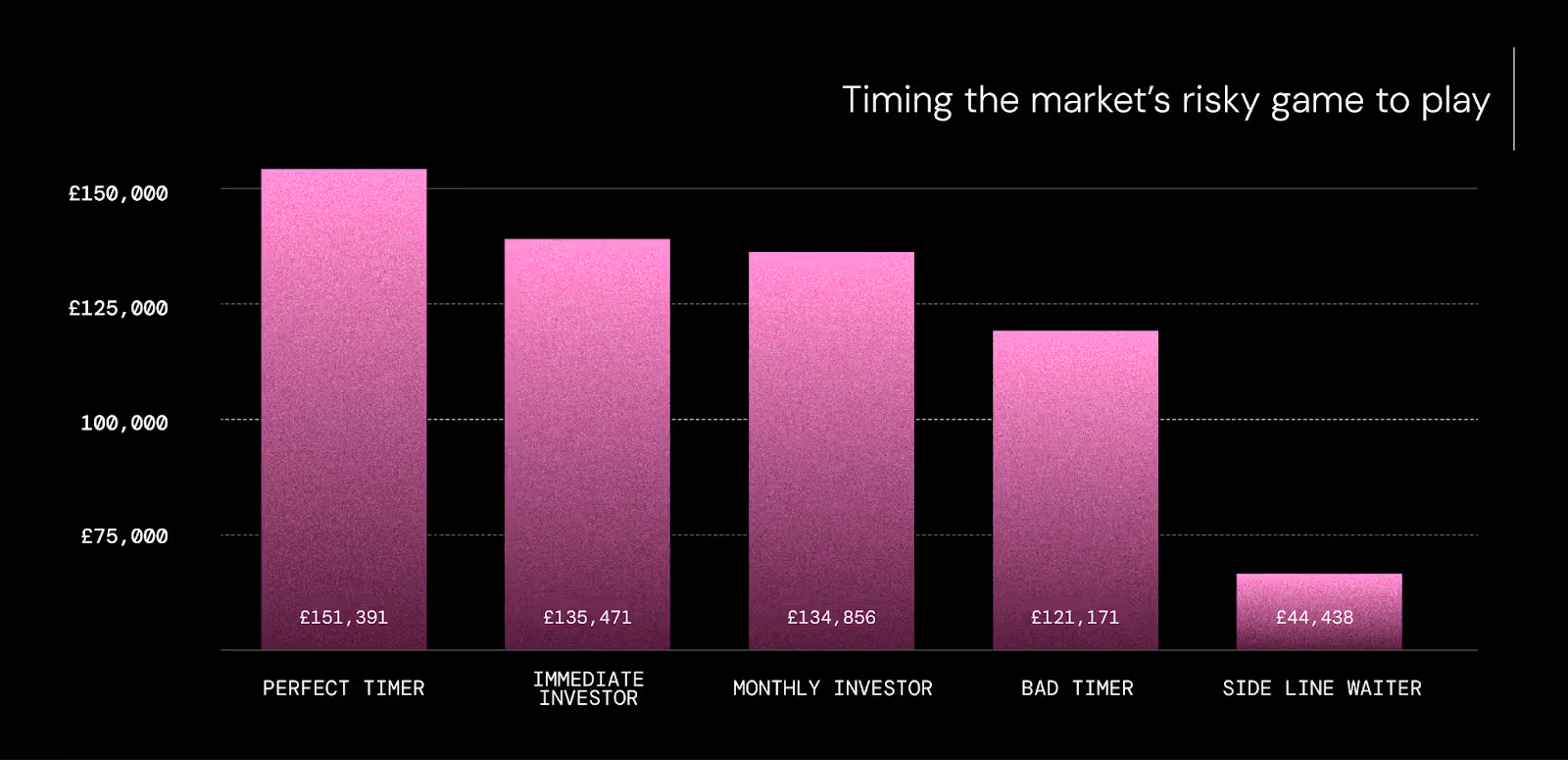

Let’s look at an example of five different investor attitudes to see how timing can lead to different outcomes.

In this example, based on research from the Schwab Center for Financial Research, five investor archetypes received $2,000 at the beginning of every year from 2001 to 2020.

- The Perfect Timer

This one's obsessed with timing the market and, because this is all hypothetical, miraculously caught every low point of the US S&P 500 index over the 20 years. - The Immediate Investor

One simply invested their $2,000 in the US market every year as soon as they got it. Simple. - The Monthly Investor

Our third investor divided their $2,000 into 12 equal portions and invested them at the start of each month. Looks a lot like dollar-cost averaging, doesn't it? - The Bad Timer

Player four had rotten luck. Trying to get the best entry points, instead, they got the worst. They invested their $2,000 each year at the top of the market, only ever catching the high points. - The Side Line Waiter

And number five was so convinced a better price was just around the corner that they never actually managed to invest in the index at all. They kept their money in US Treasury bonds instead and got stuck in limbo for 20 years.

So, who fared best?

The side line waiter invested in a hypothetical portfolio that tracks the lbbotson U.S. 30-day Treasury Bill Index instead. The index used is not intended to represent a specific investment product, so fees have not been accounted for. Dividends and interest are assumed to have been reinvested. When you invest, your capital is at risk. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns.

Does timing the market work?

A few key takeaways here, with the obligatory reminder that none of this dictates what might happen in the future in terms of investment returns.

Perfect timing won, but expecting to pick the exact right moment to invest is, to put it mildly, a little unrealistic. A timing obsessive could just as easily have been the bad timer, or even the side line waiter.

We need to go back to what we said at the start. The maths might tell us which approach gave the best returns, but there is just no accounting for real circumstances.

If we discount our ability to time the market perfectly, in the end, having your money in the market is the most important thing.

The immediate investor has the edge over our monthly saver simply because they have given their money more time to accumulate dividends and build up that snowball effect of compounding.

Again, though, most of us think about investing in terms of monthly expenditure. In that sense, setting up a monthly savings plan for your investments would have been simple and efficient over these 20 years.

Pound-cost averaging vs Lump sum investing

Pros and cons of pound-cost averaging

Advantages:

- Smooth market performance: Investing over time will smooth bumps in the market and can help to insulate you against the impact of price fluctuations.

- Suits your salary: You might find investing the same amount at regular intervals an easy strategy to slide into if you receive regular income like a monthly salary. Just ferreting away a portion of your earnings can be simpler and more stress-free than attempting to amass a lump sum before investing.

- Disciplined investing: Pound-cost averaging relies on being pragmatic and avoiding impulsive decision-making. This kind of attitude can be helpful for working towards long-term financial goals, rather than short-term wins.

- Get stuck in: Worrying about timing the market can leave you dithering and inactive, with a pot full of cash and no investments in your portfolio. Pound-cost averaging can help you over the psychological hurdle of investing your money, even if the waters are particularly choppy.

Disadvantages:

- Potentially lower returns: As shown in our previous example, pound-cost averaging may well lead to lower growth than an “immediate investor”.

- Risk not eliminated: While pound-cost averaging can smooth bumps in the market, it does not totally remove the risk of fluctuations causing losses.

- Missed dividends: If your target investment is a dividend distributor, drip feeding your money in could see you missing out on some of that regular income.

- Consider the costs: Frequent trades might see you racking up commission or FX fees. Check how much your platform charges. Freetrade does not charge commission fees, though other fees apply.

[H3] Pros and cons of lump sum investing

Advantages:

- Time in the market: “Time in the market beats timing the market”, as the saying goes. Investing all at once will allow you to reap the full benefits of compounding and dividend income from the word go.

- Investing fees: Depending on the broker you use, lump sum investing could be the cheapest option as you will avoid racking up repeated commission or FX fees.

- Simplicity: The basic simplicity of investing your money and no longer having to worry about where it is going to end up can be a psychological boon. It can help you to avoid fretting about the funds resting in your account, waiting to be invested.

Disadvantages:

- Risk of misstiming: Investing a large amount of money all at once heightens the potential impact of market volatility. If you go ‘all-in’ around the time an asset’s price peaks, you could find yourself looking at red arrows every time you attempt to assess your investment’s value.

- Can be intimidating: Lump sum investing might cause you more worry than it saves. You may end up feeling regret about your investment, particularly if the price slumps shortly after the transaction, and find yourself tinkering or panicking and selling for a loss.

- Not always feasible: Simply put, not everyone has a lump sum to invest. If you do not have a lump sum in your bank account waiting to go, you would have to put time and effort into building one.

Which is better?

According to research from Northwestern Mutual, lump sum investing beats pound-cost averaging around 75% of the time. But, by now, hopefully it's clear that we have to factor in our personal and wider circumstances here too.

Investing regularly in a set of assets takes the decision-making out of it all. It's also a great habit to stop you fiddling, getting stuck in the headlights or trying to time the perfect entry point.

It can be a particularly valuable way to invest during a bear market. There's no telling when the market will snap out of its bad mood, so edging into the market regularly means you don't have to rely on your crystal ball.

You might have a string of lower prices, but at least you aren't pinned to the first (and highest) price. What's more, as the market starts to rise, you'll break even quicker as you've been able to steadily reduce your average price.

Meanwhile, lump sum investing can also take the worry out of your decision-making and allows you to maximise your time in the market. Though research indicates lump sum investing is more likely to offer high returns, you could also find yourself at the mercy of market fluctuations and even experiencing buyer’s remorse if things go south quickly.

Remember: You do not have to pick one strategy or the other; you could do both! If you get a bonus, you might decide to invest it as a lump sum, while you could decide your salary is better invested using pound-cost averaging. Find a scenario that works for you and your circumstances.

Whatever you decide, you can open an account with Freetrade and begin investing now!

How to do pound-cost averaging

- Open an investment account, such as an ISA, SIPP or GIA.

- Look at your monthly budget and savings to decide how much you want to regularly invest.

- Automate your investments. You can do this by setting up automated payments into your investment account and then setting up recurring orders through your chosen platform.

- Resist the temptation to fiddle. One of the great positives of pound-cost averaging is that it can free you from obsessing about your investments. However, it's still a good idea to keep an eye out for ways to improve performance (such as by reducing fees), to increase your regular investments if your income improves or to consider rebalancing from time to time.

Why have a regular savings plan?

While pound-cost averaging might not always be the right strategy for you, we have noted that one of the major advantages of the strategy is that it can help you to form good habits, such as regular investing. If you've decided regular investments are for you, automating it just means one less thing to think about.

Setting up automatic recurring orders means you can leave the emotion at the door and let the process do the work for you. Here’s an example of how a regular investing habit can reward you over the long term.

ISA millionaire regular savings plan

Opening our maths books again, here's an example of how an ISA investor could reach that £1,000,000 investment portfolio. It's not a cast-iron route to seven figures by any means, and even if it's not your goal of investing, but it serves as an illustration of what a steady, long-term investment plan could deliver.

- You start off earning £25,000 at 25 years old, investing £2,500 each year until you're 30, achieving 5% returns, compounded once per year.

- At 30, you start to earn £30,000, just short of the national average salary. In your 30s, you get yearly pay rises of 3%, just ahead of the Bank of England's target inflation rate of 2%, and invest £5,000 each year.

- At 40, your pay goes up to £45,000. You keep getting yearly pay rises of 3% and put away £10,000 each year in your 40s.

- At 50, you start to earn £65,000, continue getting 3% pay rises and save £20,000 each year in your 50s.

- At 60, you start to earn £90,000 and receive 3% yearly pay rises until you retire at 65. You save £20,000 each year from 60 to 65.

- Taking into account a £5 monthly ISA fee, by retirement age, your total contributions of £460,100 have been able to snowball into a sum of £1,023,722.

Putting your cash to work over the long term makes the most of the magic of compounding. Source: Freetrade, 2022.

Pound-cost averaging vs lump sum investing - FAQs

Is pound-cost averaging the same as dollar-cost averaging?

Yes, pound-cost averaging and dollar-cost averaging are the same investment strategy. The only difference is in currency, as the former uses pounds and the latter uses dollars. Investors using the strategy in the Eurozone might likewise refer to it as Euro cost averaging.

Does Warren Buffett use dollar-cost averaging?

Warren Buffett does not rely on dollar-cost averaging, with his approach instead tending to be characterised as that of a value investor. In short, this means he sniffs out undervalued companies with the potential to generate strong long-term earnings. However, Buffett has in the past recommended it for most retail investors.

"If you like spending six to eight hours per week working on investments, do it. If you don't, then dollar-cost average into index funds."

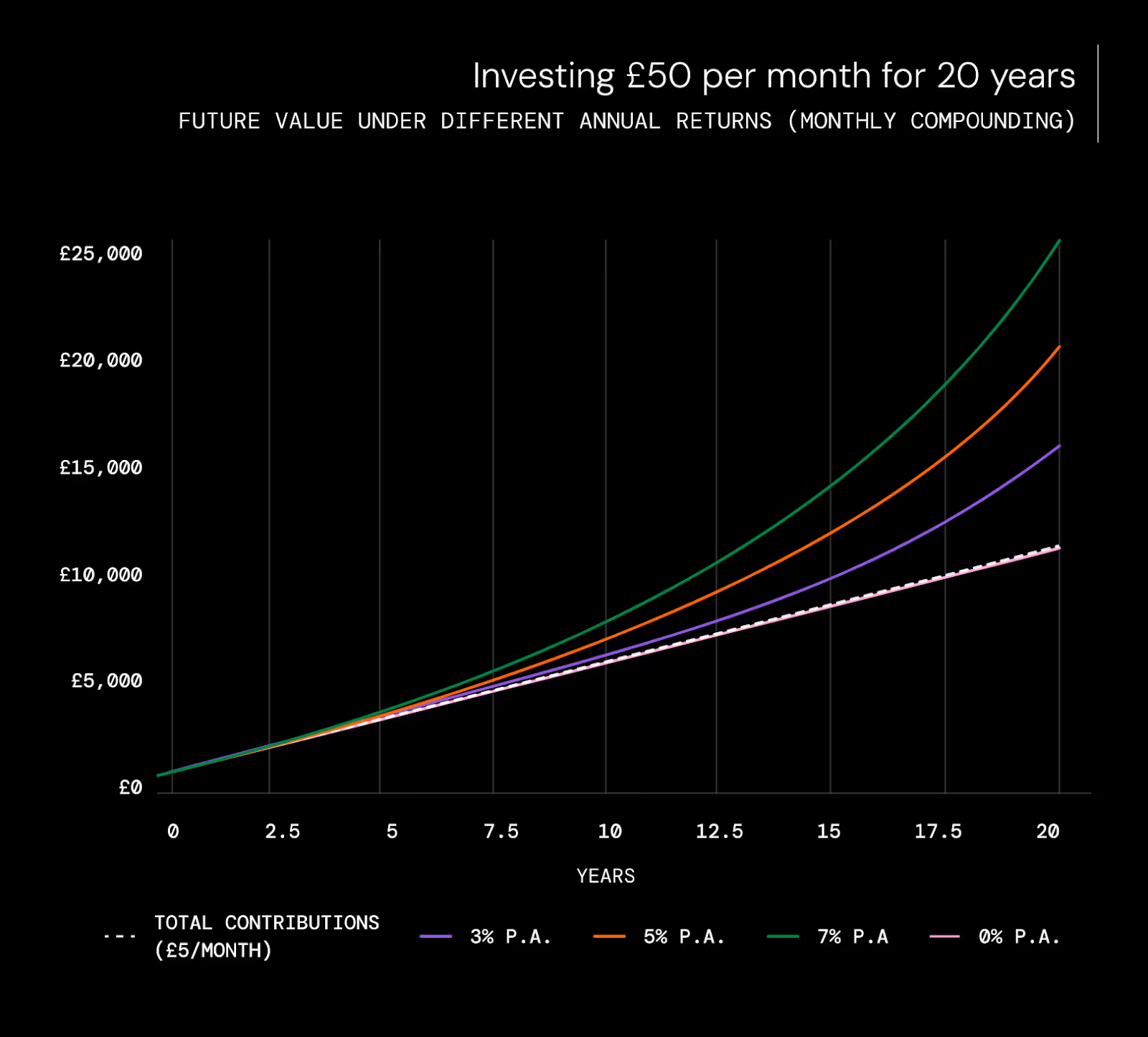

Is it worth investing £50 a month?

Investing even a relatively small amount of money each month can lead to surprisingly large returns over time. This is thanks to the steady stream of cash you are putting into your investments and the effects of compounding.

Even without any growth, you would have £12,000 set aside after two decades. Growth can lead to even stronger returns from your seemingly low levels of investing.

Find more useful information about compounding in our guide to investing in stocks.

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)