If you need a few extra pounds, you might borrow from your friend. Your friend may expect you to pay that money back. If they’re a really picky friend, they may even ask you to pay back £5 when you only borrowed £4.

In effect, a bond is similar. If a government or company goes out to investors and borrows money, bonds are issued. An investor acts as a lender, loaning an amount of money and receiving interest payments and, when the loan comes due, the full amount is repaid.

But there’s much more to how they work, how to buy them, and what they can do for your portfolio. Let’s explore what bonds have to offer to investors.

What are bonds?

Bonds are an asset class. In simple terms, they represent a loan from investors to a company, government or other entity.

An entity looking to borrow money will issue bonds in exchange for cash from investors. The borrower will typically make regular payments to the bondholder until a set date, at which point they will repay the initial amount borrowed.

Some basic key terms to know include:

- Principal and Face or Par value: The amount initially borrowed by the bond issuer, which must be repaid in full at maturity. Face value or par value is the initial amount borrowed.

- Coupon: The periodic interest the issuer must pay to the bondholder.

- Maturity: The date at which the principal is repaid, at which point coupon payments cease.

- Yield to maturity: This represents the return on investment offered by a bond. When issued, this will match the coupon rate, but once the bonds start trading, this will change as the bond’s price rises and falls.

Most bonds are tradable securities, meaning they can be bought or sold by investors. Like stocks, some can be traded via exchanges, but others are traded over the counter (OTC) - meaning they are traded directly between two parties.

How do bonds work?

That’s the basics covered, but there’s more complexity when we dig into the inner workings of how bonds work.

How are bonds priced?

There are three ways to make money from bonds. Receiving regular income, receiving the principal repayment at maturity, or selling the bond to another investor.

First off, note that bonds can trade at par or face value, and at a discount or premium (below or above face value).

Different factors impact the price of bonds, including their credit rating, liquidity risk, and interest rate expectations.

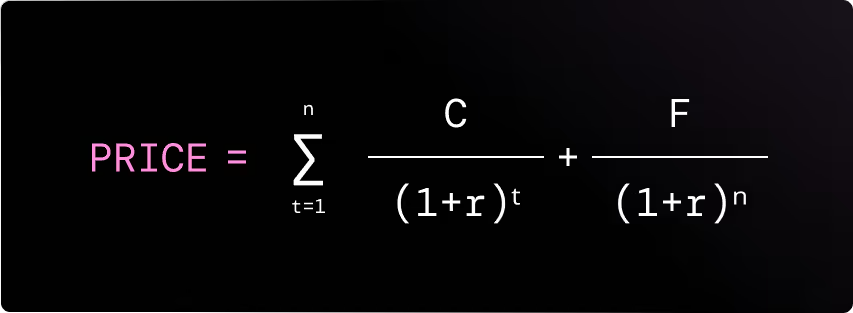

If you’re looking to break down bond valuation, you will be delighted to hear that there is also a very complicated-looking formula. It’s a formula for the present value of all future cash flows an investor can expect to receive from a bond. It looks like this:

- C = coupon payment each period

- F = face value (amount repaid at maturity)

- n = number of periods to maturity

- r = market discount rate (yield to maturity)

If you are not mathematically inclined, that looks horrible. So, let’s run through it with an example where we are looking at a bond with:

- Face value of £1,000

- A 5% annual coupon (equating to £50 per year)

- 3 years to maturity

- Market yield at 4%

As such, the bond in our example is trading at a premium (above face value). However, remember that this example ignores other factors that may impact pricing.

How do interest rates affect bonds?

Changes in interest rates can make bonds more or less attractive, significantly altering the price investors can buy and sell them for.

For example, a decline in interest rates would likely result in existing bonds’ prices rising as their coupon payments become more attractive.

In fact, we could see this in the example we used in the previous section. We imagined a bond with a face value of £1,000 and a coupon rate of 5%.

Market interest rates in the example were 4%, below the bond’s coupon rate of 5%. This made it a relatively attractive investment, leading it to trade at a premium to its face value.

However, if market interest rates were to climb above 5%, this bond would become less attractive as investors are likely to have other ways to earn the same or an improved return. In this scenario, the bond’s price is likely to fall, and it could trade at a discount, pushing its yield higher.

Why invest in bonds?

Bonds offer something a bit different in your investment portfolio. Here are some reasons investors might choose to back them:

- Diversification: Just investing in stocks or any other single asset type can open your portfolio up to significant volatility. Spreading across multiple asset classes can insulate it.

- Income: Regular coupon payments provide a reliable source of income. Investors looking for stable income, such as those in retirement, might find this appealing.

- Capital gains: In addition to regular income, there is also the chance to make money from bonds by selling them to other investors. Depending on pricing factors, investors can make gains here too.

- Risk: Bonds are generally perceived as lower risk than stocks. Some bonds, such as those backed by governments, are particularly low risk as it is perceived as less likely that a government would default on payments. This does happen, though; just look at Argentina’s history of defaults. In addition, when it comes to corporate bonds bondholders are usually repaid BEFORE shareholders in the event of liquidation, as their status as creditors supersedes shareholders’ status as owners. However, there may still be a heirarchy among a company’s different creditors.

- Defensive: Due to their perceived low risk, bonds are often used as a safe-haven asset when markets are choppy.

Bond risks

Though they may be viewed as a lower risk alternative to stocks, there are still risks associated with bond investing. These include:

- Default risk: If a bond’s issuer is unable to afford to keep paying, bondholders may miss out on coupon payments or repayment of the principal.

- Liquidity risk: Some bonds are not frequently traded. If you want to sell your bonds but trading volume is low, you may have to accept a lower price than in a more active market.

- Inflation risk: High inflation can dramatically reduce the relative value of the regular payments investors receive. Check out this example of the payments made on a centuries’ old Dutch bond.

- Call risk: With bonds that can be called before their maturity date, it’s possible the issuer may call at an inopportune time for investors.

Types of bonds

Not all bonds are built the same. Here are the three key variants of bonds you may come across:

What are government bonds?

Unsurprisingly, government bonds are issued by governments as a means of borrowing money. They tend to be low-risk, as countries are generally unlikely to default on their debt

Gilts, treasuries and more

Government bonds from different countries often have unique names. For example:

- UK: Gilts and Treasury bills

- USA: Treasuries

- Germany: Bunds

- France: OATs

- Italy: BTPs

The names may vary, but they all fall into the category of government bonds. In the UK, we call government bonds ‘gilts’ because the paper bond certificates historically issued by the government had gilded golden edges.

The UK government has never (technically) defaulted on its bonds, resulting in the term ‘gilt-edged securities’ coming to refer to very reliable investments.

What are corporate bonds?

Corporate bonds are issued by companies. They are higher risk than their government counterparts. Here is some of the key terminology used to describe them:

- Investment-grade: These bonds are at the lower end of the risk spectrum, coming with high ratings from ratings agencies.

- High-yield: Higher-risk and with lower ratings from ratings agencies, but higher potential returns. Also sometimes unceremoniously referred to as ‘junk bonds’.

- Convertible: Indicates that a bond can be ‘converted’ into a certain amount of the issuing company’s shares by the investor.

- Callable: Indicates that the issuer can repay the principle prior to maturity, paying off their debt early. A company might choose to do this during periods of low interest rates, allowing them to refinance their debt to reduce coupon payments.

What are municipal bonds?

Municipal bonds are issued by local government authorities and other public organisations in order to fund public works projects. While generally considered to be low risk, they are not as secure as some government bonds.

What are zero coupon bonds?

While coupon payments are the norm, there are some bonds which offer no regular income. These zero coupon bonds simply offer the return of the principal at maturity. However, because there is not regular income payment, these bonds are often issued at a discount.

This means a buyer could purchase a zero coupon bond for £700, but receive £1,000 at maturity. Though they have not received income from regular coupon payments, they have achieved a £300 return.

Treasury bills

Treasury bills are a common form of zero coupon government bonds. In the UK, these are issued weekly (generally on Fridays) by the Debt Management Office. They have a fixed term and UK treasury bill maturity is typically in 1, 3, or 6 months. However, they can technically have maturities of between 1 and 364 days.

You can invest in UK treasury bills through Freetrade.

How to invest in bonds

You can invest in bonds through many different brokerage accounts. Check out the Freetrade app for a variety of bond investments.

Another way to invest is by using ETFs or mutual funds, which will allow you to quickly diversify and invest in different asset mixes.

Learn more by reading our investor’s guide to mutual funds.

What is a bond - FAQs

Do you pay tax on UK bonds?

Many UK bonds are exempted from capital gains tax.

- UK government bonds/gilts: These are exempt from capital gains tax.

- Qualifying Corporate Bonds (QCBs): Certain corporate bonds, known as QCBs, are not subject to capital gains tax. These must meet certain requirements, including being expressed in sterling, representing a normal commercial loan and include no provision for currency conversion.

However, income tax is still payable on regular coupon payments received from the bond issuer.

Meanwhile, capital gains tax is payable on profits earned by selling non-UK bonds or non-qualifying UK corporate bonds.

For maximum tax efficiency, bonds held within a tax-efficient wrapper like a Stocks and Shares ISA or Self Invested Personal Pension (SIPP) are exempt from these taxes.

If you’re not sure about your tax position, you should speak to a tax professional.

How much money should you keep in bonds?

There is no set amount of money investors should have in bonds. You should make a choice based on your own circumstances and attitude to risk.

That being said, some investors will favour heavier or lighter weighting toward bonds depending on their financial goals. As bonds usually offer greater stability and lower risk, an investor might favour a more bond-heavy portfolio as they approach retirement to mitigate the impact of market turbulence.

How do bonds make you money?

Investors can make money from bonds by collecting regular income from coupon payments, collecting principal repayments when a bond matures or is called by the issuer, or by selling the bond to another investor.

Can you sell a bond before maturity?

You can sell a bond before maturity using your brokerage account. The amount you sell it for will depend on factors such as face value, interest rates, maturity date and market conditions.

The value of your investment can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. ISA and SIPP rules apply. Tax treatment depends on your personal circumstances and current rules and may change. A SIPP is a pension designed for people who want to make their own investment decisions. You can normally only access your money from age 55 (57 from 2028). Freetrade currently only supports Uncrystallised Fund Pension Lump Sums (UFPLS) for SIPP withdrawals. Seek professional advice if you need help with your pension.

-%25201000x750%2520(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.jpg)