Since the crash in February and March of last year, lots of commentators have been anxiously saying that the disconnect between the US stock market’s performance and the reality of its tanking economy can’t continue.

And yet it has. The S&P 500 continues to hit record highs and finished 2020 up 16%.

Money keeps flowing into the markets too. We’re not even at the end of January and there have already been several multi-billion dollar IPOs, like Playtika and Driven Brands.

Doom and gloom

It could be easy to look at all of this and say the naysayers were wrong.

And to an extent, they have been. If you’d kept your money out of the markets in 2020 then you’d have missed out on some serious growth opportunities.

But the problem with talking about bubbles is not necessarily figuring out that we’re in one but predicting when it’s going to burst.

The late president of Israel Shimon Peres liked to say that you should only make predictions 50 years ahead. If you end up being wrong, either you’ll be dead or people will have forgotten what you said.

Clearly that was meant in jest but there is a kernel of truth to it. It’s often easy to predict a trend or event but very hard to say when exactly it will happen.

For instance, Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan expressed concern that there was a stock market bubble in 1996. He may have been correct but it didn’t burst for another four years.

And therein lies the trouble for today’s commentators. It may be the case that we’re in a bubble today but it’s practically impossible to say when it will burst.

Wait….are we in a bubble?

This makes it sound as though it’s easy to say when we’re in the midst of a market that’s far too overvalued.

But what really constitutes a stock market bubble?

A simple way to define it would be when share prices are so high that they go beyond the realistic current and future earnings potential that a business has to offer.

By that metric, it’s not unreasonable to think that we may be in one.

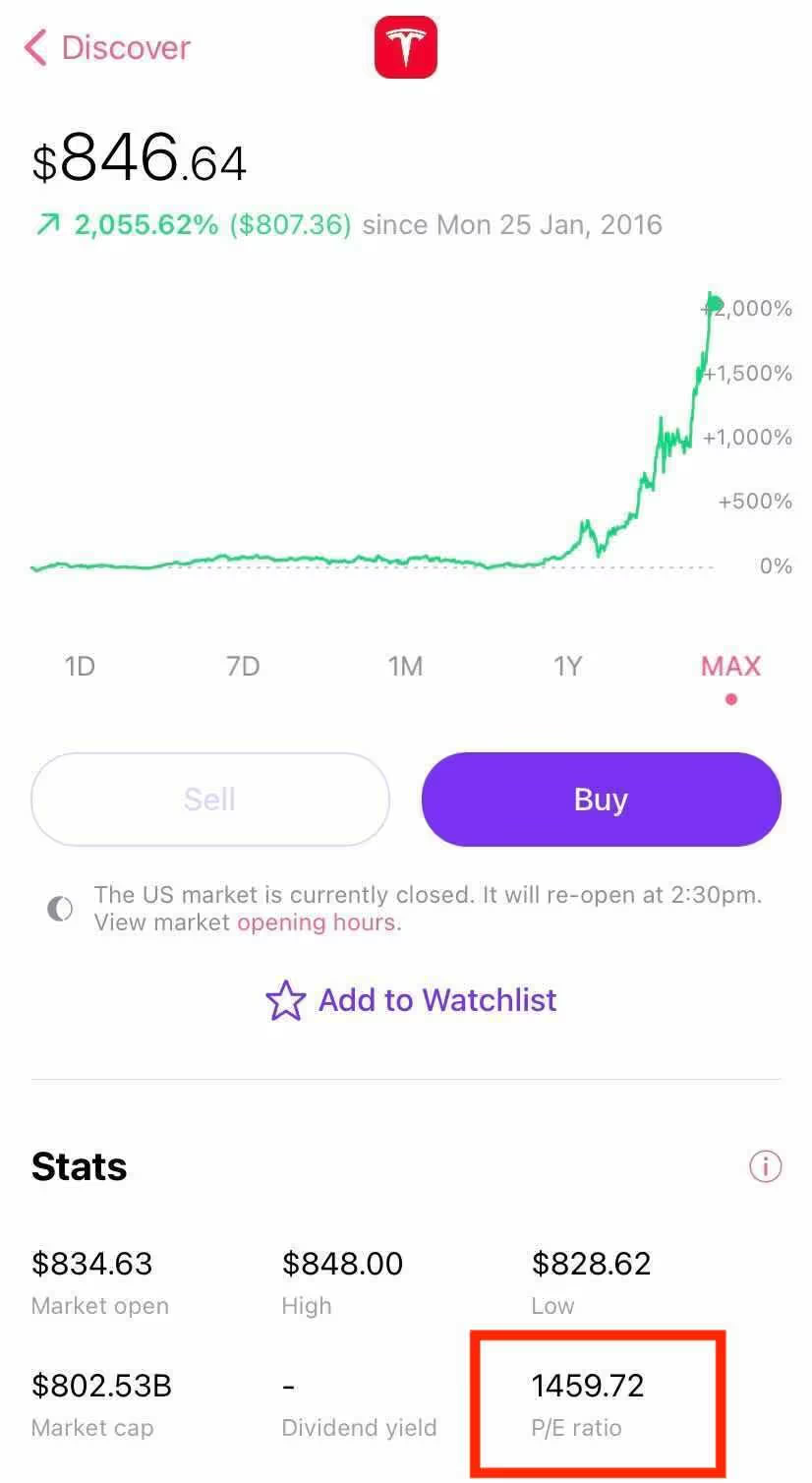

The analysis firm Cresmont Research published data at the end of December showing that price-to-earnings ratios are at their highest level since the dot com crash in 2000. And aside from that year, they’re at the highest levels the market has seen in the past 120 years.

A price to earnings ratio tells you how much you have to pay for a company’s shares relative to how much money it makes. So if a company has a P/E ratio of 10, it means you are paying £10 for every £1 that the business earns.

That may seem odd but it’s normal to pay several times what a company makes for its shares. That’s because your investment will be taking into the account the total value of the business, plus its future growth opportunities.

But if P/E ratios rise massively, it’s often a sign of overexuberance on the part of the market.

If investors end up pumping money into any old firm, it causes their shares to become overvalued relative to their future earning potential.

The bubble bursts when investors realise this and begin selling off their holdings to capture profits before the price comes down again to its ‘true’ value.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that a business caught up in a bubble is bad, just that it’s overvalued.

For instance, Tesla shares are now regularly trading at 1,500x earnings. Clearly the carmaker is innovative and likely to do well in the future. But such a massive gap between its earnings and share price is hard to justify.

Tech leads the way

Of course, the focal point of much bearish angst over the past few months has been the tech sector.

Huge increases in the value of companies like Alphabet and Apple has led to claims that we’re in the midst of another dot com-style bubble. Famous investor Barry Sternlicht made this exact point last Thursday.

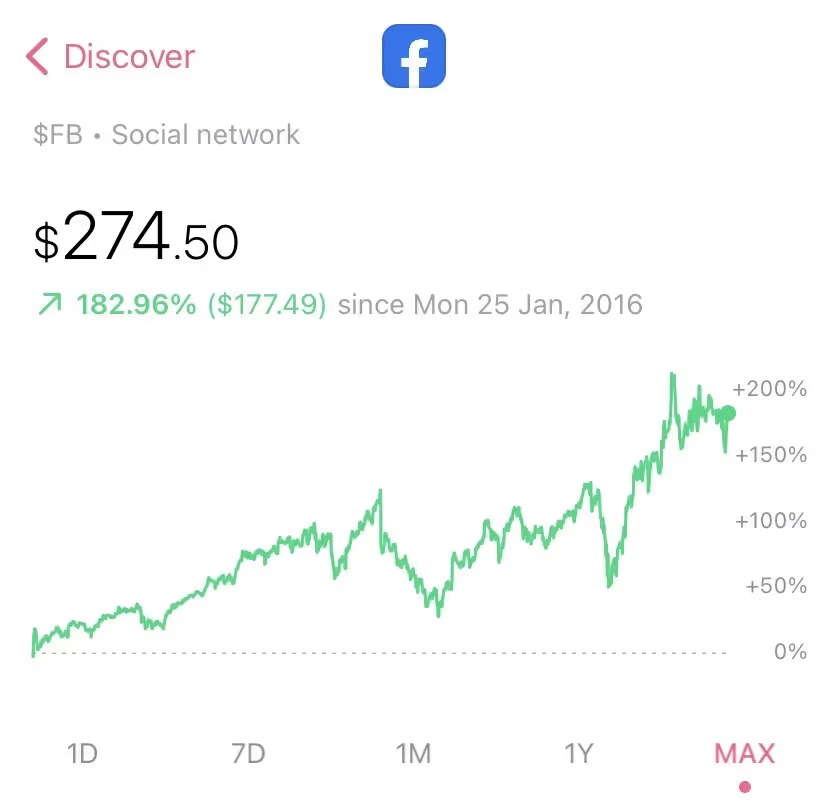

The trouble is that tech companies keep proving these people wrong. Facebook, for instance, continues to regularly post double-digit percentage growth in revenue.

Even Netflix, which was criticised for its finances, managed to reassure shareholders last week when it posted massive growth in its number of new users and said that it wouldn’t take on any more debt.

Microsoft, Apple and Facebook are all posting financial results this week. They’ve typified the flight to tech so far, but again the question isn’t whether they are popular or not, it’s whether they’re overvalued.

That being the case, more optimistic investors may say that the high valuations we’re seeing, at least when it comes to tech, are justified because those firms keep growing and making lots of money.

What to do?

All of this may leave you scratching your head a little.

Are we in a bubble? Are we not? If we are, when will it burst?

This last question is probably the most important one to answer. Lots of people try to ride the wave a market bubble creates and cash in at its crescendo.

The trouble with doing this is that you have no idea when it might burst and, if you mess up, you can end up losing a huge amount of money.

One way to mitigate this is to simply sell out of positions you think are overvalued or risky and keep your holdings in cash.

True, you might miss out on some subsequent growth.

But it would be better to miss out on tomorrow’s single digit growth if it meant risking double digit losses the day afterwards.

Bubbles are also a reminder that putting all of your money into one market is a very risky business. It’s why you need to consider assets that are varied in terms of their type, geography and industry.

Keeping cash to hand, so that you can meet all of your expenses, is vital.

But holding a range of assets can offset losses too. Gold, for example, does not generally crash if the stock market does. Similarly, companies in Asia or the UK are less likely to be affected to the same extent by a fallout in the US tech sector.

In short, predicting exactly when something is going to happen isn’t easy and trying to build an investment strategy around that is a foolhardy thing to do.

But taking steps to mitigate the risks associated with an event happening at some point in the future is likely to save you money (and stress too).

At Freetrade, we want to make it easy and accessible for everyone to invest in the stock market. That’s why we built our stock trading app from the ground up and focussed on helping customers achieve better, long-term financial outcomes. Start with an investment account or a tax-efficient account like an investment ISA or a SIPP pension.

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)