Maybe the London property market deserves a break.

Are prices overinflated and exorbitantly higher than the average local can afford? Certainly.

But have you considered the amenities? Sure, the water in the pipes is a smidgen calcified and it’s cheaper to buy 10 new jumpers for layering rather than pay to heat the place.

At least you can see and feel a bit of that bang you get for your buck though.

A couple of weeks ago, a 6,090 sq. ft. waterfront plot of land in Decentraland sold for $2.4m.

As you may have guessed by its name, Decentraland is a decentralised (so, powered by the Ethereum blockchain) digital community. It’s a 3D virtual reality platform made up of 90,601 parcels of land, each of which is its own NFT, which can be bought and sold through the cryptocurrency, MANA.

Metaverse Group, a self-coined digital real estate firm, bought that plot for the highest asking price of all time. The Group’s plan is to build a storefront and event space on it, and eventually host digital fashion shows and sell virtual clothing for avatars on the platform.

If all this seems far fetched, maybe even a bit suspect, perhaps it is. It can be hard to wrap your brain around the idea of investing in something if you can’t grasp it, let alone grab it.

With clothes, money and real estate going digital, it’s tempting to see this notion of investing in ‘nothing’ as a new phenomenon.

While it’s certainly revving up, buying into a dream is nothing new.

Getting on track

If you hop into your time machine and set the dial to 1840, railroads were a very hot investment.

It would have been easy to buy a share, and to believe you knew exactly where that money had gone. The physical growth of the track is easy to visualise - each additional piece laid, gauge by gauge and tie by tie.

Then consider buying a modern-day share in a tech behemoth like Microsoft.

If you’re hoping for an equally clear picture of where your investment’s going, you’re probably out of luck. How exactly that capital would bolster the firm’s Word or Excel software is much more unclear.

The comparison of the two vastly oversimplifies oversimplification. The belief that an investment in something ‘tangible’ makes it a safer or more reliable one is a false narrative.

A trainwreck

Railway Mania was a stock market bubble that overtook the UK in 1840. It worked as most bubbles do: railways were taking off, and speculators wanted a bigger piece of the pie. Parliament saw this happening and was licking their chops at the prospect of plenty more pounds in the bank.

So they pushed full steam ahead, setting up a fleet of new railway companies to try and meet the demand.

With the influx of firms entering the market, Parliament (very falsely) claimed they could build another 9,500 miles of track. Investors, seeing green, just kept buying more shares. This of course jacked up share prices even more - until eventually, they collapsed.

A third of the railroads were never built - either due to being fraudulent fronts in the first place, simply not having enough capital and resources, or being bought out by the other fakes.

All growth starts from nothing

All that goes to show investing in a physical good won’t always protect you from actually buying into zilch. Given that dated example, this willingness to believe in the vision of what a company is doing or selling, even when we can’t see it with our own eyes, is far from a blockchain era fad.

It’s a core tenet of what growth investing’s all about: pursuing firms exhibiting signs of future above-average growth.

Valuations can often seem high, given how little a lot of these firms actually have under their belt, but the theory is they will grow into their share price and keep the earnings coming.

Lost in SPACs

So it’s nothing new, but our level of ease for investing in a vision has definitely been pushed into overdrive. The SPAC boom is good evidence of just that.

In the purest sense, a SPAC is a cash shell. It aims to acquire a private company and take it public without the usual paperwork required of an IPO.

As an investor, that means you won’t have access to much knowledge about the potentially acquired firm in question, which renders conducting any due diligence next to impossible.

True to their name, in exchange for a share, these “blank cheque companies” will offer you some space on the dotted line, but not much power in deciding who that signed cheque’s getting mailed to.

It’s a mystery box, and as an investor, you’re along for the ride.

But the extreme uncertainty here doesn’t seem to have perturbed investors.

In 2020, SPACs secured $83bn in funding, making up 46% of all US IPO proceeds and 55% of the year’s listings. By March of this year, SPACs had already smashed that record. And as of October, US SPACs had raised a whopping $138bn.

Life’s like a box of chocolates

The eye-rollers in the old school equity brigade might not be keen on the prospects for SPACs.

But it’s a little too easy to dismiss the newest vehicle on the block because you think you know better. In fact, complacency is a great sign of hypocrisy.

While the traditional IPO of a firm with several years of sales could give a firmer sense of what you’re investing in, that’s not always the case.

Rivian’s IPO last month raised nearly $12bn with an initial offering of $78 per share. It was the biggest IPO for an American company since Facebook. And what’s the firm got to show for it?

In its October 22 prospectus, Rivian had produced 56 and delivered 42 of its R1T electric trucks. While the firm at least has a physical product on its hands now, its exorbitant valuation clearly doesn’t rest upon the fact it’s manufacturing on average two cars a day.

Rather, it’s a reflection of Rivian’s order book, in which you might spot 100,000 units next to the word ‘Amazon’. Again, the idea is that investing in nothing now will pay off in spades later.

The firm has a very long way to go to reach that level of output and scale though.

While it has proven it can get something to market, there’s a big difference between concept and lightning pace production. Just ask Henry Ford or Mr. Musk.

Rationally irrational

This isn’t to say it’s impossible but if zealous investors are letting their pumping hearts rule their heads, it isn’t actually vastly different from investing in an invisible plot of land, or a currency based on a tiny golden dog.

Our hopes and desires for something to work out can often outweigh our rational mind’s yearning, and frankly, ability, to bring us back down to earth.

It’s especially tempting to believe that a company will eventually pull off what it claims it can, when there’s so much on the line if it can’t.

Dr. Market will see you now

Biotech firms looking to go public capitalise on precisely that. Often, still years off from public trials, they can IPO at valuations based on the assumption of some impending success.

In the same vein as SPACs, 2020 was an especially great year for the industry. Covid surely led to plenty of eyeballs on biotechs, raising awareness for many firms previously flying under the radar.

Lockdowns also ushered in an unprecedentedly strong desire to believe in those firms purporting they could put this whole thing to rest.

Partly, they’re easy claims to rationalise because our will to believe them is just so big. Partly, it’s pretty hard for the everyday investor to understand what on Earth these firms are actually doing.

Looks Merck-y

Your biology 101 textbook may have offered a rough sense of what a double-blind trial is, but how comfortable do you feel assessing the investment-worthy merits of: “Week 144 data from the Phase 2b dose-ranging study evaluating the antiretroviral activity, tolerability, and safety of islatravir in combination with doravirine compared to doravirine/lamivudine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (DOR/3TC/TDF) in antiretroviral treatment-naïve adults with HIV-1”?

Those words plucked straight from a recent press release at Merck, the alleged Covid pill treatment maker, are enough to have you wondering whether it just dropped a fully tiled Scrabble board.

As an investor, understanding all the jargon and terminology thrown about by the firms you invest in is not a prerequisite. Though it’s pretty important that you at least get the big picture, which is especially tough when the firms don’t have that on lock just yet either.

Increasingly, that’s the case for many new firms entering the market.

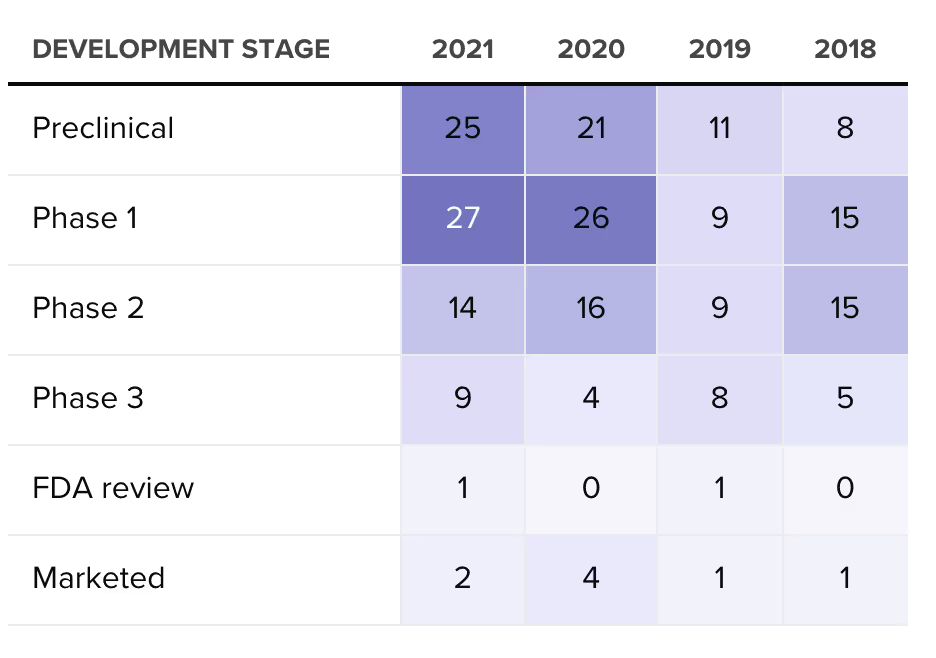

25 preclinical stage firms IPOd in the US this year, all of which are pre-human trials. Meaning, at a stage where they're purely testing the general feasibility and safety of their prospective product.

They’re still a long way off entering phase one trials, let alone securing regulatory approval to begin marketing, or generating revenue.

Of the firms who actually do manage to land clinical trials, the US Congressional Budget Office reported only 12% will snag the coveted FDA stamp of approval.

That means the remaining 88% don’t have a product to bring to market. As an investor, that brings about a lot of uncertainty for what’s next, and a fairly terrifying pill to swallow.

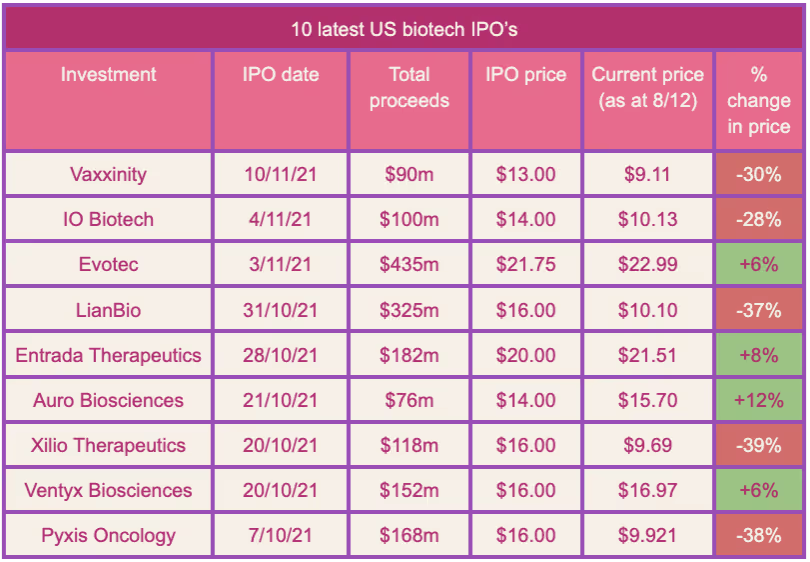

When you consider America’s most recent 10 biotech IPOs, that nightmare seems a bit more real. Many are struggling to keep up with their initial valuations, and of those who’ve pulled off some gains, it’s still a fairly uncertain road ahead.

Turns out a lot of us have been investing in nothing for quite some time.

Head in the clouds

Your primary school teacher wasn’t wrong when they pumped you full of reminders for the importance of dreaming big.

When you invest, you shouldn’t be investing in a company’s past performance. That’s not a reliable indicator of future returns.

Nevertheless, you do need to be able to decipher just how much of a company’s dream has an actual shot of becoming reality.

Asking yourself how you feel about the people running the business, the product they’re trying to make, and the people they’re going to serve are some good starter questions.

If you can’t confidently answer those yourself, it might be because the firm’s done a bad job explaining itself.

That puts you at a higher risk of drinking the Kool-Aid. Sometimes, it won’t taste so bad. There are copious examples of firms with rags to riches stories - those who’ve beat the odds with groundbreaking innovations that the naysayers would have never thought possible.

But that's not always going to be the case. And there are thousands of other options on the investor’s shelf, many of which aren't cyanide-laced, and could leave you with a much more comfortable return.

As an investor, your job isn’t to luckily land on the winners, it’s to develop a consistent and repeatable process that brings you back when you eventually succumb to the allure of nothing.

When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.If you are unsure whether a product is right for you, you should contact a qualified financial advisor.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)