In 2008, Brazilian businessman Hermes Magnus was looking for investors.

He had just started exporting electrical components and needed two million reals (about £640,000 at the time) to grow his business.

He eventually ended up at an office run by two Lebanese-Brazilians named Alberto Youseff and José Janene, the latter of whom was a major politician before he died in 2010.

Magnus managed to secure investment from the pair but he soon realised he was receiving far more than he had asked for.

Moreover, the money, much of which was coming from huge cash deposits, was being used to overpay for various goods, some of which he didn’t even need.

Growing suspicious that he had unwittingly been caught up in a money laundering operation, Magnus reported what was going on to a local judge.

Shortly afterwards, he received death threats, lost his business and had his home burned down in an arson attack. He fled Brazil and seems to have been given asylum in the US.

Six years later, he was watching the news and saw Alberto Youseff pop up on his TV screen.

The currency dealer had been arrested on money laundering charges and was seeking a plea bargain.

What followed was the largest expose of corruption in Brazil’s history.

The cases stemming from the investigation, which are still ongoing, would see ex-presidents arrested, Brazil’s wealthiest man go bankrupt and lead to mass protests across the country.

And at the heart of all of this was one company — Petrobras.

Petróleo Brasileiro

The Brazilian Petroleum Corporation, Petróleo Brasileiro Société Anonyme in Portuguese or Petrobras for short, is Brazil’s largest company and its biggest oil producer.

It was founded in 1953 under the slogan “o petróleo é nosso” — “the oil is ours.”

That slogan is indicative of the policies that were being pursued by the Brazilian government at the time.

Under the quasi-dictatorship of president Getulio Vargas, Brazil had been strongly nationalist and corporatist. One of its main goals was to develop strategically important industries in Brazil and keep them Brazilian.

It was this ideological driver that also led Vargas to set up national steelmaking, carmaking and chemicals producing companies in addition to Petrobras.

Monopoly

Petrobras enjoyed a monopoly in the Brazilian hydrocarbons business for almost half a century.

Like many government-controlled monopolies, it was criticised as being inefficient and badly managed. For example, the firm spent $350 million in the early 90s on a gigantic oil rig that blew up and sunk not long after it went into action.

The Brazilian government eventually changed the regulations governing the oil industry in 1997 and, two years later, foreign energy companies started doing business in the country.

But this policy was partially reversed in 2007.

That was because the ruling Workers Party, a far-left group that had opposed deregulation, wanted Petrobras to maintain control of a large group of recently discovered oil fields.

Dilma Rousseff, who would later become president, gave Petrobras sole operating rights in the fields and mandated that they would have a minimum 30 per cent stake in them too.

Another policy put in place was that 85 per cent of all equipment, tools and materials used in the oil fields had to be produced in Brazil.

To be fair, this was not necessarily a bad policy. It does seem to have created lots of jobs for Brazilians and helped develop local industries.

The problem was that it also allowed for obscene levels of corruption.

“If I speak, the republic is going to fall”

Unbeknownst to him, the tip that Hermes Magnus gave to a judge back in 2008 led police to wiretap Alberto Youssef’s phone.

Youssef had already been involved in several money-laundering and embezzlement cases but had always managed to escape prison.

The wiretap that police placed on his phone bore fruit when Youssef talked about bribing a senior Petrobras executive, Paulo Costa, with a Range Rover.

Costa would ultimately become a key witness in helping bring down corrupt officials in government and business.

Youssef was also arrested. Speaking with his legal team, he famously said, “if I speak, the republic is going to fall.”

The Car Wash

Youseff did speak (and the republic kind of fell too).

What he revealed was a huge network of corruption that was in part due to the regulations that the Workers’ Party had put in place.

In simple terms, Brazilian companies would massively overcharge Petrobras for goods and services.

The excess money would then be funnelled off to different people, including Petrobras officials, business executives and politicians. By one account, the Workers’ Party received $200 million in kickbacks from the scheme.

The police investigation would become known as ‘Operation Car Wash’.

The name was taken from a currency exchange, attached to a car cleaning business, that was used by people in the scheme to launder their ill-gotten gains.

Fallout

The impact from the Car Wash scandal was huge and its effects are still being felt today.

Lula, Brazil’s former president, was sent to prison. Rousseff, who was president when the investigations began in 2014 and had been Petrobras’s chairman, was impeached in 2016.

One of the key witnesses was Marcelo Odebrecht, the CEO of Odebrecht — a huge Brazilian conglomerate that is involved in construction, engineering, real estate and more.

Odebrecht (the CEO) was sentenced to ten years in prison (reduced from 19 years in return for details on bribe-takers) for paying $30 million in bribes to Petrobras executives.

His testimony implicated hundreds of people, both inside and outside of Brazil.

For example, the heads of both major political parties in Peru were implicated and Alan Garcia, a former Peruvian president, shot himself in the head after police came to arrest him.

In Brazil, Operation Car Wash led to huge protests across the country in 2015 and 2016. Many have also said that the scandal was a huge factor in the election of Jair Bolsonaro, who was not involved in any cases stemming from the investigation, in 2018.

Petrobras today

One of the most remarkable things about the Petrobras scandal is how soon it came after a period in which Brazil was riding high.

The country’s economy was growing at a far faster rate than most of the developed world and, along with the other so-called BRIC countries, China, India and Russia, Brazil was being pushed as a success story for emerging markets.

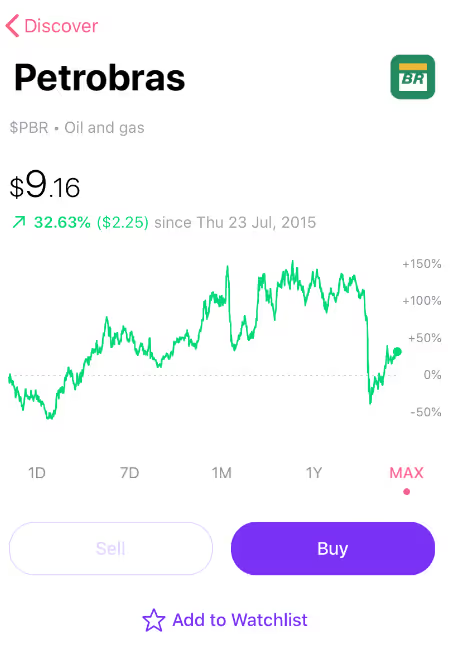

Petrobras was a big part of this narrative. The oil firm was listed in 2000 but offered more shares to the public in 2010. At the time, this was the largest fundraising round ever made.

Investors piled $70 billion into the company, making it the fourth-largest in the world by market cap, though the Brazilian government remains the majority shareholder.

Unfortunately for those investors, Petrobras shares dropped by $70 billion in value in the year following the start of the scandal.

A small part of that decline was due to a decrease in oil prices but, when you compare Petrobras’ performance at that time to other big oil businesses, it’s clear that Operation Car Wash was likely the main factor causing investors to flee.

Picking up the pieces

Given the magnitude of the corruption at the firm, it may seem surprising that Petrobras is still a listed company.

The oil company did almost go bankrupt in 2016 but ultimately managed to secure debt financing.

The size of the firm — it’s still Brazil’s largest company and deeply intertwined with the local economy — meant that it could hardly be disbanded. Moreover, the revelations may not have been too shocking to some.

Brazil was not renowned for being a straight-laced place to do business and most Petrobras investors probably knew that there was some less than scrupulous behaviour taking place at the firm, even if they were surprised at the scale of it.

The shadow of the Car Wash scandal continues to hang over the business but things have been more positive since economist Castello Branco was appointed CEO in early 2019.

The executive has managed to meet targets and boost revenues, though COVID-induced lockdowns and the consequent lowering of oil prices have hit the firm hard in 2020.

Another potential positive for the firm is the prospect of privatisation. Bolsonaro’s economic team is packed with Chicago school economists, all of whom have been pushing for the Brazilian government to privatise state assets.

Petrobras is the largest of those assets and several reports indicate the Brazilian president wants to privatise Petrobras by the end of his term in office.

He looked likely to succeed in this endeavour too. But, to paraphrase Mike Tyson, everyone has a privatisation plan until they get hit by a pandemic.

Some Brazilian lawmakers have also been curiously opposed to privatization efforts.

To be fair to them, selling a company during an economic crisis is not a great idea because you aren’t going to get the best price for your assets.

If, however, those politicians continue to prevent the sale of state assets in the future, it may be worth wondering if the mantra of the “oil is ours” continues to reign supreme amongst Brazil’s political class.

We believe investing should be accessible to everyone. Whether you are a complete beginner or an experienced investor, there’s something for you at every step of your journey. We’ve covered choosing the right investment app, what are dividends and how to invest in ETFs. You’ll also find step by step guides on buying and selling stocks, as well as an ISA explainer and a ‘SIPP vs ISA’ guide to help you decide which account is best for you.

Important information

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.

When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)