With demand for vaccines, medicines and medical equipment rising, many of the companies selling those products have seen a commensurate increase in revenues.

One such business is Hikma Pharmaceuticals.

The UK listed company announced that it would be increasing its half-year dividend to $0.16 per share on Friday, a 14 per cent increase on the same dividend from last year.

That decision came on the back of an 18 per cent increase in revenue during the first six months of 2020 compared to the same half-year period in 2019.

What is Hikma Pharmaceuticals?

For people in the UK, who are accustomed to ‘free’ healthcare from the NHS, the idea that you can make money from medicine may seem crass. But it’s big business.

The NHS spent £129 billion last year. A substantial portion of that money is used to pay staff but a lot goes to private companies that sell the drugs and equipment that doctors and nurses need to do their job.

The UK is not unique in doing this. All medical professionals and institutions need products to do their job. Hikma Pharmaceuticals is one of the companies that supplies them.

The firm sells a mixture of generic drugs.

In layman's terms, a generic drug is one on which the original patent has expired.

That means other companies are free to make copies of it. Paracetamol, for example, is a generic drug, which is why you can see shops like Boots and Tesco selling their own branded versions of it.

Hikma sells both branded and non-branded generic drugs. So you might be able to buy drugs that have the Hikma brand on them or they’ll make the drugs for other companies that then put their own branding on to it.

A short history of Hikma Pharmaceuticals

Hikma — which means ‘wisdom’ in Arabic — was founded in Amman, Jordan’s capital city, in 1978.

The company was started by Samih Darwazah, a Palestinian born to a tea merchant in the city of Nablus.

Incidentally, Palestinians are well-known for being active in the pharmaceuticals industry. In Israel, where they make up a fifth of the population, more than half of all pharmacists are Palestinian.

Darwazah studied in Beirut and then opened a pharmacy in Amman. In 1964, however, he managed to get a scholarship to study pharmaceuticals in St Louis.

Once he was done, he got a job at the pharmaceuticals giant Eli Lilley. He spent the next 12 years at the company, working in the US, Europe and the Middle East.

The idea for Hikma came when he realised that there was a demand in Jordan for cheap generic drugs that wasn’t being met.

He set up the business with $1 million in capital but initially struggled.

The problem for Hikma was that, although there was a demand for cheap generic drugs, the facilities that produced them in Jordan were not well respected.

Darwazah’s solution was to invite the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which regulates the US pharmaceuticals industry, to their factory.

The FDA gave its seal of approval, Darwazah sent copies of the document proving this to every doctor in Amman and Hikma got off the ground.

Trading peanuts for drugs

Hikma’s founder often said that he got industry experience from Eli Liley but knew how to do business because of his tea merchant father.

A huge part of Hikma’s success does appear to have been due to Darwazah’s business acumen, as opposed to the firm actually creating new or revolutionary drugs.

The Hikma founder made a famous deal in the 1980s when dealing with some Syrians. At the time, Syria was in an economic crisis and experiencing double-digit inflation.

Rather than accept the increasingly valueless Syrian pound as payment, he traded Hikma’s products for marble and peanuts, then sold the commodities on for a profit.

Entrepreneurial flair aside, Hikma was also very aggressive in expanding through acquisitions.

Initially, the pharmaceuticals firm only sold generic brands in the Middle East. A mixture of local know-how and cheaper prices helped the firm along the way.

Over time, however, the company started buying other businesses. It acquired firms in Europe, the US and in multiple countries across the Middle East and North Africa.

This increased the range and volume of drugs that it was able to produce. At the same time, it meant that Hikma could start operating in different markets.

On the public market

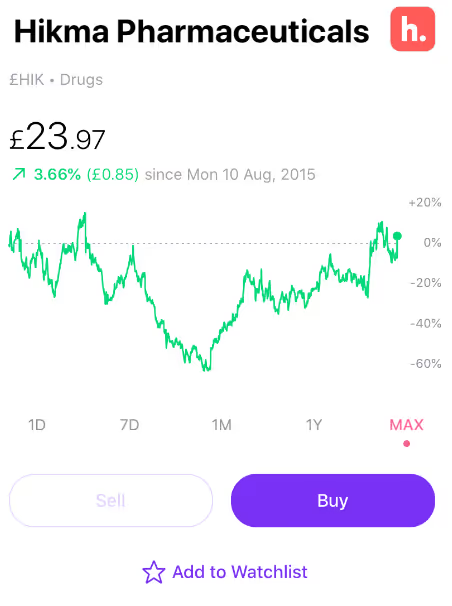

Almost thirty years after its founding, Hikma went public on the London Stock Exchange in 2005.

The firm’s shares initially traded at £2.90. Today they’re priced at £24.23.

This doesn’t mean it’s been all smooth sailing for the firm — far from it.

The pharmaceuticals company got its first big boost on the stock market when it acquired the Egyptian Company for Pharmaceuticals & Chemical Industries in 2013.

Huge growth in the revenue of its US business a year later also helped the firm’s shares rise in value.

Hikma shares reached an all time high of £26.43 in July of 2017.

But in the following months, disappointing profits, Brexit and disparaging comments about “big pharma” from then presidential candidate Hilary Clinton saw the company’s stock price slide down to £16.

After recovering slightly in the following six months, the company’s shares tanked again after a downgrading from analysts at JP Morgan, who warned about growing competition in the global generic drugs market.

Perhaps more damaging was a controversy surrounding the use of its products for lethal injections in the US. The company has said repeatedly that its products were misused and that it was not selling drugs to authorities for that purpose, though this doesn’t seem to have appeased investors.

Shares in the company bottomed out at £8.58 in early 2018, before rising steadily upwards to £17.28 in March of this year. At that point, shares in the pharmaceuticals firm shot up as investors tried to put money into the businesses that were more likely to profit from the pandemic.

They were ultimately rewarded for their endeavours by the most recent revenue announcements.

That said, the 15 years that the company has been on the stock market show the huge range of things that could happen that may put a damper on any further increases in its share price.

Healthcare remains a near-sacred topic all over the world, blurring the lines between business and morality, which means companies like Hikma are subject to a greater level of scrutiny than many other businesses.

Surviving in such an environment, along with strong competition, can be tough. Still, if the company retains the peanuts-for-drugs spirit of its founding father, it’s more likely to be able to pull through the hard times.

At Freetrade, we want to make it easy and accessible for everyone to invest in the stock market. That’s why we built our stock trading app from the ground up and focussed on helping customers achieve better, long-term financial outcomes. Start with an investment account or a tax-efficient account like an investment ISA or a SIPP pension.

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)