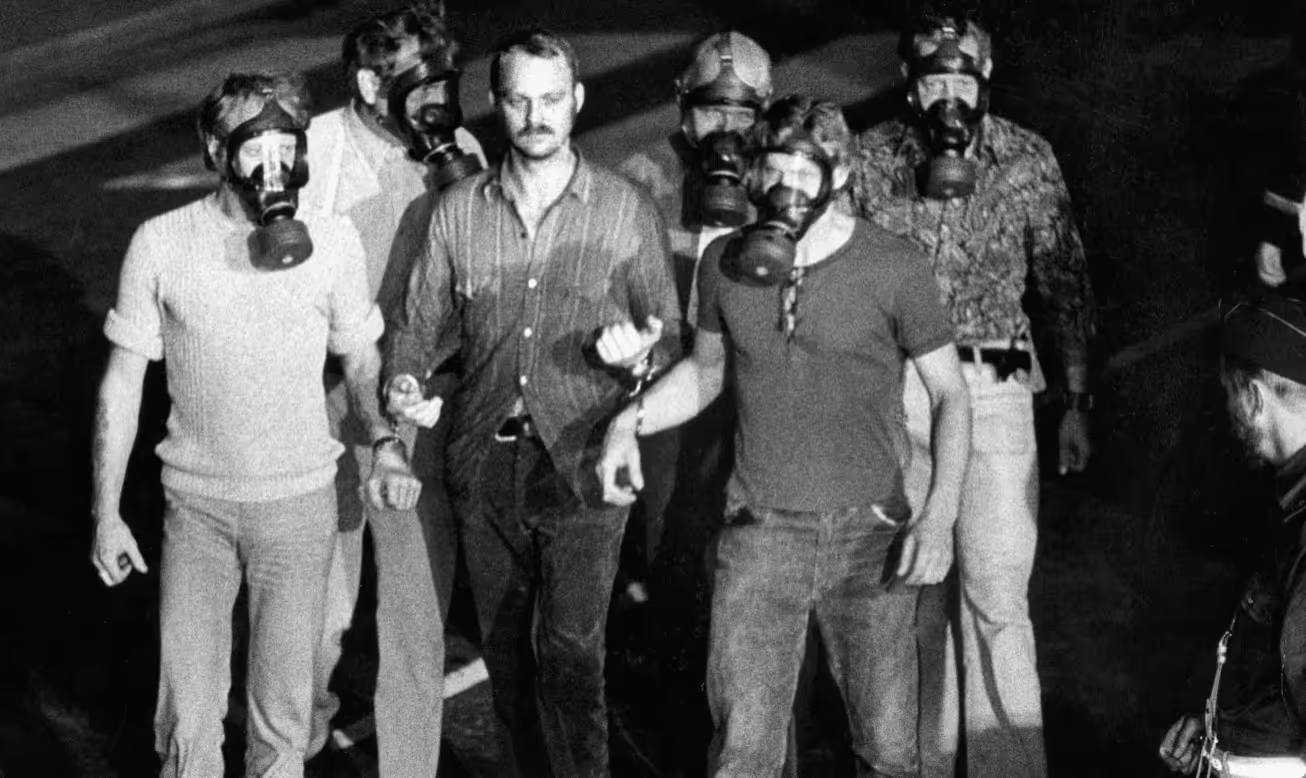

In August 1973, safe-cracker and escaped convict Jan-Erik Olsson walked into a bank in central Stockholm, unveiled a submachine gun, fired at the ceiling and yelled, “The party has just begun!”

The ensuing six-day siege, during which Olsson held four people hostage, ended rather bizarrely when the hostages tried to protect their captor.

“When he treated us well,” said hostage Sven Safstrom, “we could think of him as an emergency god.”

The hostages actually began to fear the police instead of Olsson and were hostile towards an officer allowed in to make sure they weren’t injured.

Stockholm syndrome has been a weird cultural reference ever since and shows just how malleable our minds are when exposed to extreme levels of stress and uncertainty.

If Olsson had been clinical and cold, it’s likely the hostages would have kept their distance. But offering a jacket to a shivering prisoner and consoling her when she had a bad dream (seriously) broke down that barrier.

He even allowed one claustrophobic hostage to walk outside while attached to a 30-foot rope. She later told The New Yorker, “I remember thinking he was very kind to allow me to leave the vault.”

Stockhold syndrome

The amazing thing here is that Olsson was the source of all negativity. Yet all it took was some simple personable acts to get the bewildered hostages onside.

There are very real, albeit less life-threatening, parallels with how we deal with stressful situations on our investment journeys.

It’s a realm never short on stress if you haven’t prepared yourself mentally and, crucially, is rife with the opportunity to fall in love with your kidnapper.

How that tends to play out in our accounts is the same too, through overfamiliarity. The longer we hold a stock, the more likely we are to develop our knowledge of the company, its management, its financials, its sector and can talk confidently over dinner about why we hold it.

Read more:

You hold too many stocks

Share buybacks: don’t be a fool

Sign up to Honey, our daily market newsletter

As that relationship grows, it can sprout a couple of problems. The first takes the form of the sunk cost fallacy. We’ve put so much effort into building that relationship that we see it as a complete waste of time and energy if we sell out and move on.

I daresay the same could apply to our human relationships but that’s a topic for another day.

If our ‘favourite’ stock (a phrase we should never utter) runs into trouble for good reason rather than the general ups and downs of market life, we can opt for the losing position over the cut-throat decision to sell just because of familiarity. Better the devil you know and all that.

We come up with all sorts of excuses and reasons to stay invested, and listen to any advice as long as it supports our choice to stick around.

Investing isn’t a team sport

The past few years have seen a novel development in the world of putting money into risk assets. There are now factions ready to paint their faces and wave their team’s flag, as well as spew vitriol at anyone brave enough to tweet anything other than complete allegiance.

This has tended to pop up in two specific areas - electric vehicles and cryptocurrency. We won’t use a beautiful morning like this to pitch their pros and cons against one another, after all that’s not the point. Regardless of the asset, developing too close a bond with it is a recipe for psychological torment.

It’s something the pros wrestle with too. Lindsell Train co-founder Nick Train has made it very clear that he probably should have sold publisher Pearson a number of times over the past few years.

Believing too much in its ability to evolve and maintain leadership clouded his ability to see the value it was destroying for him and other shareholders.

The stock doesn’t know you own it

As soon as we let go of objectivity, our actions inevitably start to be run more and more by our emotions.

We then tend to entrench those views no matter what that asset does, a bit like sports fans revelling in victory and finding a kind of melancholic comfort in loss; “they’re my team and I'll back them through thick and thin.”

The exact same thing can happen in your relationship with a stock.

The point is though, it’s not your childhood team. It’s a tool. As Peter Lynch says, the stock doesn’t know you own it. It has no allegiance to you and won’t perform better or worse due to your unwavering fanaticism.

Treat every company in your portfolio as a tool to be used when necessary and replaced when it no longer serves a purpose.

Strap on your investment toolbelt

A good way to reduce emotional attachment is to give yourself strict buy and sell criteria. That could be putting a ceiling on the P/E ratios you will allow in your portfolio or even identifying the non-negotiables in specific investment ideas.

If a certain arm of a business is the reason you bought in, spinning that division off might be a clear reason for you to thank it for its service and move on.

Sticking with it just because you don’t want to have to look at something new just isn’t good enough.

That’s where a watchlist comes in handy too. It can be easy to get rid of an underperformer if you already have an idea of what could replace it.

Guestlist only

Remember, companies should be fighting for the chance to get into your portfolio and having a bank of prospective additions in the wings is a good way to make sure you only have your best ideas on show at all times.

That might mean having a few companies in the background that you like, but just don’t meet the entry requirements just yet. Valuations might be a bit too high or there might be a short-term corporate hurdle for them to clear before you give them the green light.

If they suddenly fall into your investable range, you’ve done the due diligence and can snap them up in the knowledge that logic drove that decision, not emotion.

Whatever your process is, don’t stay bound to a bad idea just because it’s the one you know through and through. Have the objectivity and confidence to keep the quality high in your portfolio and say goodbye when you need to.

We think investing should be open to everyone. It shouldn’t be complicated, and it shouldn’t cost the earth. Our stock trading app makes it simple for both beginners and experienced investors. And costs are low. You can buy and sell shares commission-free and take advantage of fractional shares (buy just a part of a share). Download our iOS trading app or if you’re an Android user, download our Android trading app to get started investing.

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)

.avif)