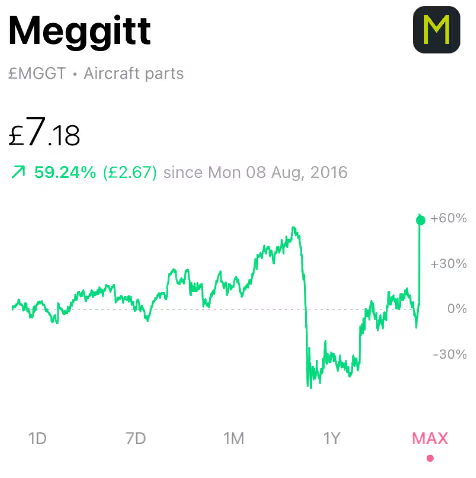

Meggitt is not the sort of company that usually makes headlines.

Themakes different components, like brake controls and engine systems, most of which are used for planes, particularly in the defence sector.

But this week the company was in the news after it announced it was subject to a takeover bid from US rival Parker Hannifin.

The deal will see Parker Hannifin paying £8.00 per share for Meggitt.

When those terms were announced, Meggitt’s shares were trading at £4.69, meaning the acquisition could result in a 71% gain for shareholders selling their stake in the firm.

Private equity is on the scene

This was not an isolated event. US firms have been rushing into the UK market over the past year in an effort to snap up a whole range of businesses.

Around the same time Meggitt announced its proposed takeover, the bougie fitness brand Sweaty Betty confirmed it had been acquired by Wolverine Worldwide, a US footwear manufacturer.

Both of these takeovers, assuming they go through, will see two companies in similar industries merging together.

Although this can be problematic, the more controversial deals we’ve seen have involved private equity funds.

This is what looks likely to happen with Morrisons, which is pushing its shareholders to accept a £9.3bn takeover bid from Fortress Investment Group.

And even though it’s probably the most notable example, it’s far from the only one. Private equity funds have struck more deals in the UK so far this year than at any other time on record.

Why is this happening?

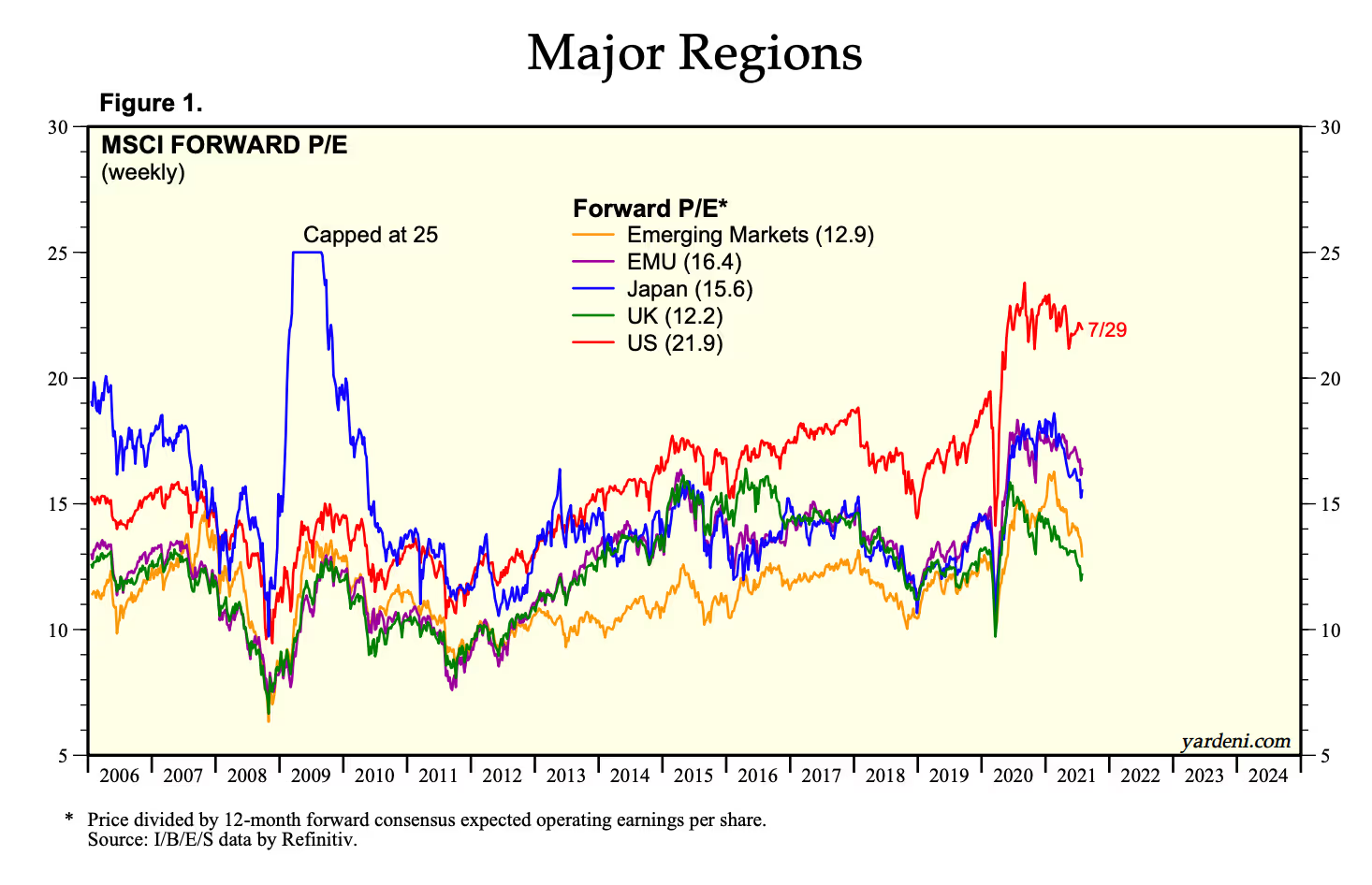

Probably the biggest cause of this buying spree is the UK market’s relative cheapness compared to other major economies.

London-listed shares are trading at an average price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, a figure which compares a company’s share price to its profitability, of just over 12. For comparison, the US average is 21.9.

Part of the reason for that is the unattractiveness of many UK shares.

Tobacco and oil stocks, for instance, make up more than 10% of the UK primary index. These are not the sorts of businesses investors expect to see massive growth in the future, so they tend to trade at lower P/E ratios.

Brexit arguably has had a hand in things too. The UK’s decision to leave the European Union was not well received by institutional investors, both because of the uncertainty it caused and fears about what the consequences would be.

At the same time, the pound has weakened since the 2016 referendum, making shares sold in sterling cheaper than they once were for foreign investors.

Last year’s Covid-induced market crash compounded this as it pushed down share prices even more.

The effect of these different factors has been to dampen UK stock valuations, even in companies that still run solid businesses and which may offer growth opportunities.

And when these sorts of firms are on offer at lower prices, it’s common to see private equity starting to get involved.

Vultures circling

Not everyone is keen on private equity funds. Terms like ‘vulture’ and ‘robber baron’ tend to get thrown around whenever they roll into town.

Sometimes such epithets aren’t unwarranted. Many private equity funds buy businesses using borrowed money. They then secure those loans against the assets of the company they’re taking over, saddling the firm with debt. This is what was done with the retailer Debenhams in the early 2000s.

Another common trick, often done in conjunction with the above, is to asset strip a company. This is when a private equity firm sells off the assets a company holds, usually paying out the proceeds as a dividend.

They often then relist the firm on the public markets, cash out immediately, and leave other people to pick up the pieces.

What’s particularly objectionable about this process is that private equity firms typically have a model which means they stand to gain an outsized portion of any subsequent gains generated from the sale of a business.

But if asset stripping leads to a situation where the company goes under, they bear almost none of the cost. It’s a case of heads I win, tails you lose.

Lots of people are worried this is what may happen to Morrisons. The supermarket chain owns a lot of the real estate its shops are located on. Private equity firms may sell that off, get the shops to lease back those properties, and then keep the proceeds for themselves.

Turning things around

Private equity funds obviously don’t see themselves in such a negative light, nor do all of them engage in the sort of behaviour we’ve just described. Many funds see an opportunity to buy a business on the cheap and turn it around for greater long-term profitability.

Fortress has implied this will be its goal if it does end up taking over Morrisons. The thing is, we’ve heard similar promises from private equity firms in the past and they’ve ended up being broken not long afterwards.

Softbank said it would be investing in Arm for the long-run when it acquired the UK chip designer in 2016. It sold off a Chinese subsidiary two years later and is now in the process of selling the rest of the business to Nvidia.

For us regular investors, this often produces an ethical dilemma. It’s common for private equity funds to pay more for a company’s shares than the price at which they’re trading.

If you’d bought shares in Morrisons before the terms of deal with Fortress were announced, for example, you could be in line to make a 42% gain on your investment.

That might be great for you. But what if Fortress does ultimately engage in asset stripping and then flip the firm back on to the public markets saddled with loads of debt?

You may have made some money but the consequences of this could be hundreds of people losing their jobs or a massive hit to the company’s pension fund.

Making money is obviously great but if these sort of negative societal consequences come as a result of it, then you have to question whether there may be more important things at play than a 42% gain in your portfolio.

What do you think of the Morrisons deal? Let us know on the community forum:

Source: FE, as at 5th August 2021. Basis: bid-bid in local currency terms with income reinvested.

At Freetrade, we want to make it easy and accessible for everyone to invest in the stock market. That’s why we built our stock trading app from the ground up and focussed on helping customers achieve better, long-term financial outcomes. Start with an investment account or a tax-efficient account like an investment ISA or a SIPP pension. Download our iOS stock trading app or if you’re an Android user, download our Android stock trading app to get started investing.

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)