Will a shift to nuclear power lead to rising uranium stocks?

Ongoing attempts to reduce reliance on Russian oil and gas have hastened conversations about the green energy transition. The EU will soon cut all ties to Russia’s coal and oil, and Russia’s retorting by cutting some of its gas exports in return.

So, how will countries power their energy grids? And where will that energy come from?

The looming energy crisis (or current, depending on the country you call home) has sped up the debate over the best way to confront dwindling energy supplies at surging costs.

Some argue countries will increasingly need to localise their power sources where possible. And many will be pursuing green energy alternatives in efforts to abide by net-zero plans. That means there are a lot of eyes on wind and solar alternatives.

The problem is, not all countries have sufficient resources of either to generate power. But theoretically, nuclear energy can be generated anywhere.

Are we transitioning to nuclear power?

That’s one reason why the UK has been debating whether nuclear might be key to achieving net zero ambitions. Boris Johnson seems to believe so, making a very ‘Euro 2021’ -esque claim that nuclear is “coming home”.

The UK already has plans to build eight new reactors costing £13bn so that it can source 25% of the nation's energy from nuclear power by 2050.

There are a few reasons why nuclear’s being touted as a better alternative to other energy sources.

A nuclear power plant runs thanks to nuclear fission, a process undergone when uranium releases a massive amount of heat and radiation energy. That energy powers a turbine, which in turn generates electricity. No greenhouse gases (GHGs) are emitted in the nuclear fission process.

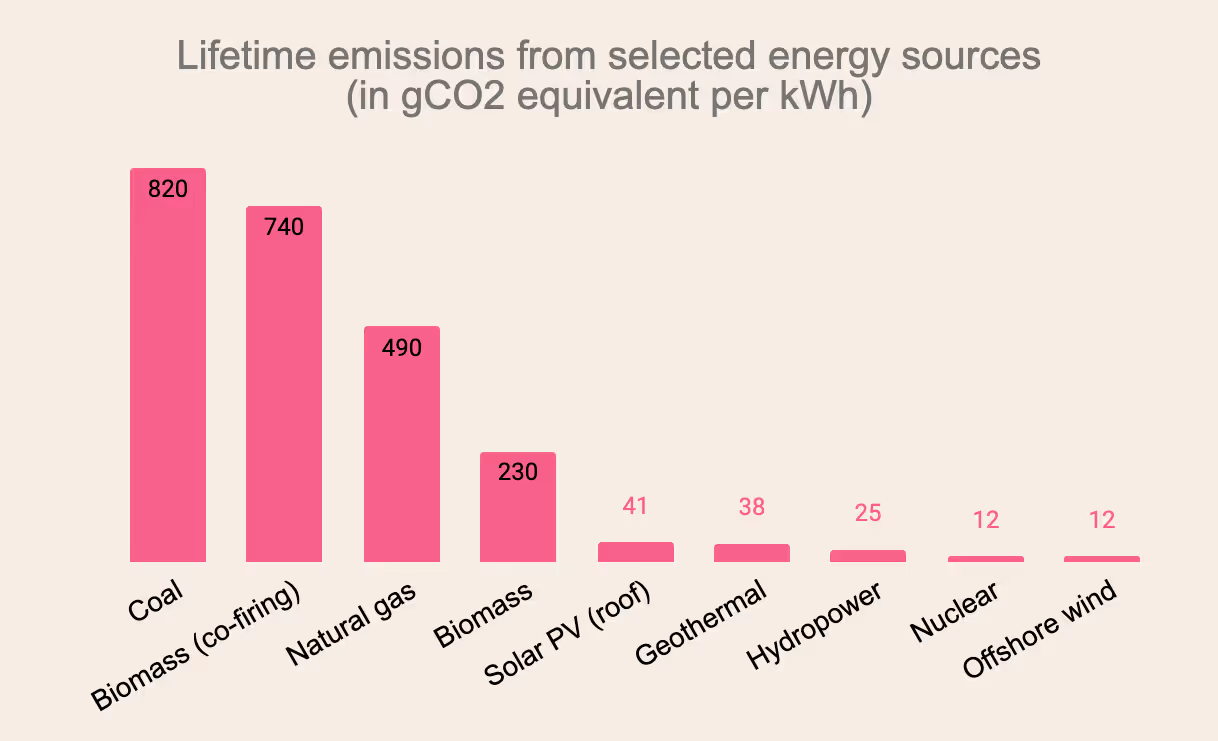

Although mining and refining required to obtain uranium have a decent carbon footprint, once full lifetime emissions are considered, nuclear energy’s pollution is on par with offshore wind. That makes it a very low polluting energy source when assessed relative to its energy generation.

A nuclear plant can operate at 93% capacity, while wind turbines tend to be around the 40-50% capacity range.

That unpredictability is a major factor in the UK’s struggles to source the energy needed right now through offshore wind. Renewables were supposed to provide 18-20% of the nation’s electricity, but lately, winds aren’t blowing in our favour. Turbines are only providing 11% of the energy entering the UK’s grid.

What is Uranium?

Uranium is a naturally occurring radioactive metal and a bit like global stock markets of late, Uranium is unstable. It’s found all over the planet and according to Livescience is the 48th most abundant element found in the earth's crust.

Kazakhstan is the world's largest miner of uranium by some distance. It mines over 22,000 tons a year, more than three times the next biggest producer, Canada.

Uranium for electricity

None of this is to say nuclear doesn’t come without risks. Nuclear waste and the radioactive by-products from power creation have deadly consequences if not stored or disposed of properly.

The radioactivity of that waste gradually decays over time, but it can take thousands of years to completely be disposed of.

The high-level waste (known as spent fuel) made of metal rods is formed by uranium pellets. That’s the uranium that actually generates the electricity. Though increasingly, countries are finding additional uses for the pellets after they’re done creating the energy. China, Japan, Russia and parts of Europe are now recycling these tubes.

And they can also be used as low-carbon energy once recycled. This process can neutralise a lot of the concerning radioactivity. As for any waste that isn’t recycled, it’s usually deposited underground and sealed with clay.

The grave nuclear disasters our planet has witnessed cannot be understated either. In an array of disasters around the globe, lives have tragically been lost as nuclear reactors have gone awry and natural disasters have destabilised power plants.

Factors influencing the price of uranium

In the wake of the 2011 Fukushima tragedy, Germany and Japan closed their nuclear reactors. Nuclear power is still controversial in both countries, with just three of Germany’s 17 power plants remaining open and set to close by the end of the year.

With many countries veering from nuclear in response to the devastation, the demand for nuclear fuel slowed. For a while, that also resulted in the uranium price plummeting.

A huge glut of uranium followed. With a massive supply overhang to work through, the price of uranium faltered for years after. Though the tides have been turning over the past few years, as nuclear power becomes considered a viable, and perhaps vital, green energy alternative for some nations.

Lately, some nuclear power stocks have been jumping up the charts.

That’s because as the price of uranium increases, uranium producers should benefit,. particularly existing producers with the capacity to mine more. As demand revs back up, uranium miners are increasingly turning their machines back on. And investors are taking note, especially as the uranium spot price hits multi-year highs.

Which uranium companies can you invest in?

Many popular uranium mine stocks are listed across the big stock exchanges and can be found on your Freetrade app.

Before we get stuck in though, it’s important to highlight that this is a wrap-up, not a suggestion or recommendation that you buy or sell any of the securities mentioned.

Remember, everyone has their own goals and unique financial circumstances. These, along with your tolerance for investment risk and time horizon, should inform the mix of assets in your portfolio.

Our resource hub for investing in the stock market might be able to help make that blend a bit clearer for you and our guide on how to invest in stocks is a great start for first-time investors. And if you are still unsure of how to pick investments, speak to a qualified financial advisor.

Top uranium stocks

Here’s a rundown of some popular uranium stocks on Freetrade. This is not a list of the best uranium stocks to buy. It’s just a collection of some of the nuclear and uranium mining stock investments on Freetrade that can offer investors exposure to the commodity and power source.

These stocks vary in their degree of involvement with uranium and nuclear power. They also span a number of different countries. It’s important to know what you’re looking for when it comes to investing in uranium, because some are purely exposed to the commodity’s price, which can carry a heightened level of risk.

1. Yellow Cake

Yellow Cake invests in physical U3O8 (or Triuranium octoxide, a compound of uranium). It isn’t a miner, it’s a passive investor in the commodity.

Investors in Yellow Cake gain exposure to the element’s price while avoiding risks involved with exploration, development, mining and processing of the material.

Yellow Cake’s profitability depends on the uranium spot price. In a way, it can be thought of as a trust, with a calculable net asset value (NAV) for all of the U3O8 it holds. So if its stock is trading at a price below its NAV, then it’s at a discount. If it’s above, then it’s at a premium.

In its latest quarterly report, the firm’s U3O8 was valued at $57.90/lb. Given its 15.8m holding, that meant its estimated NAV was $1.1bn. At that time, Yellow Cake’s net asset value per share was £4.40, and it was trading at a price of around £4.00 per share.

So theoretically, its shares would have been at a discount relative to its uranium holdings at that point in time. That might be because of the heightened risk of investing in the commodity and its especially volatile price.

Ultimately whether at a premium or discount to NAV, it’s the price of uranium that will dictate the success or failure of Yellow Cake.

And as demand for uranium ramps up alongside the now-depleting supply, Yellow Cake could benefit by rising prices. And with no net debt, it could be in a better place to finance future contracts.

But since its Q1 earnings were released in April, Uranium’s price fell a fair bit from its 11-year highs.

The firm is taking a long view though. Yellow Cake is forecasting a uranium supply deficit by 2030, crossing its fingers that its “buy and hold” strategy will really pay off then. And in preparing for an impending shortage, Yellow Cake just increased uranium holdings by about 3m lb. by the end of June.

Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future returns.

Source: FE, as at 22 June 2022. Basis: bid-bid in local currency terms with income reinvested.

2. Cameco

Cameco is an alternative way for investors to get exposure to uranium for their portfolios. The Canadian firm explores, buys, mills, and sells uranium, with Yellow Cake being one of its customers.

Cameco already has plenty of uranium in its reserves. So if demand does indeed continue to grow, it should be well-positioned to sell it at a higher price to buyers. Especially compared to newer firms with fewer reserves.

However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has led to increased price volatility in the uranium market. The unpredictability of changes in Russian uranium supply, and uncertainty over which countries will continue to import it, add a massive layer of uncertainty to that market.

As countries diversify their power supply away from Russia, Cameco might have some more eyes on its uranium. The US, UK, France, South Korea and Belgium all plan to expand the duration of their existing nuclear reactors, building more while they’re at it too.

The US sourced over 20% of its uranium from Russia in 2020. And while Biden has banned imports of Russian fossil fuels, he hasn’t banned Russian uranium imports. So for now, the country is still reliant on Russia, but if that changes, firms like Cameco could become increasingly vital for other countries’ energy supplies.

At this point, this nuclear stock needs the price of uranium to grow along with more long-term contracts to secure its future. It’s still only operating at 60% of its capacity and plans to do so until it secures a home for the commodity.

3. Energy Fuels

This miner is the largest US producer of uranium. Energy Fuels has a few additional revenue streams too, like producing vanadium, a material used in steel, alloys, and grid-scale batteries. It’s also investigating whether radioisotopes can be used in emerging cancer therapies.

So it has a fairly varied pipeline of business streams but selling U3O8 is its bread and butter. Energy Fuels sells uranium to firms, which then process it into fuel for nuclear reactors.

The firm believes the US will soon reduce ties with Russia’s state-owned nuclear company.

If so, Energy Fuels thinks it's positioned to benefit. As a US-based uranium supplier, the country’s $6bn nuclear credit program would likely (at least in part) go towards purchasing from Energy Fuels supplies.

But the US hasn’t opted out of Russia yet. And so in the meantime Energy Fuels has been selling some of its vanadium inventory over the past months, with the commodity’s price also exhibiting volatility since Russia’s invasion.

The firm sold 150,000 lbs. of vanadium this quarter at an average price of $11 per lb., which it was carrying at a value of around $5.40. While that might be a decent margin now, there’s no guarantee those prices will stick around.

The recent rise is thought to be related to increasing Chinese demand from infrastructure.

Even though China just ordered a $120bn credit line to fund infrastructure growth, when one country holds a lot of demand in the palm of its hand, a lot is out of a business’s control.

4. Rolls-Royce

The mind might wander to flashy white phantoms when Rolls-Royce gets name dropped, but the publicly traded company is entirely separate from its automobile division.

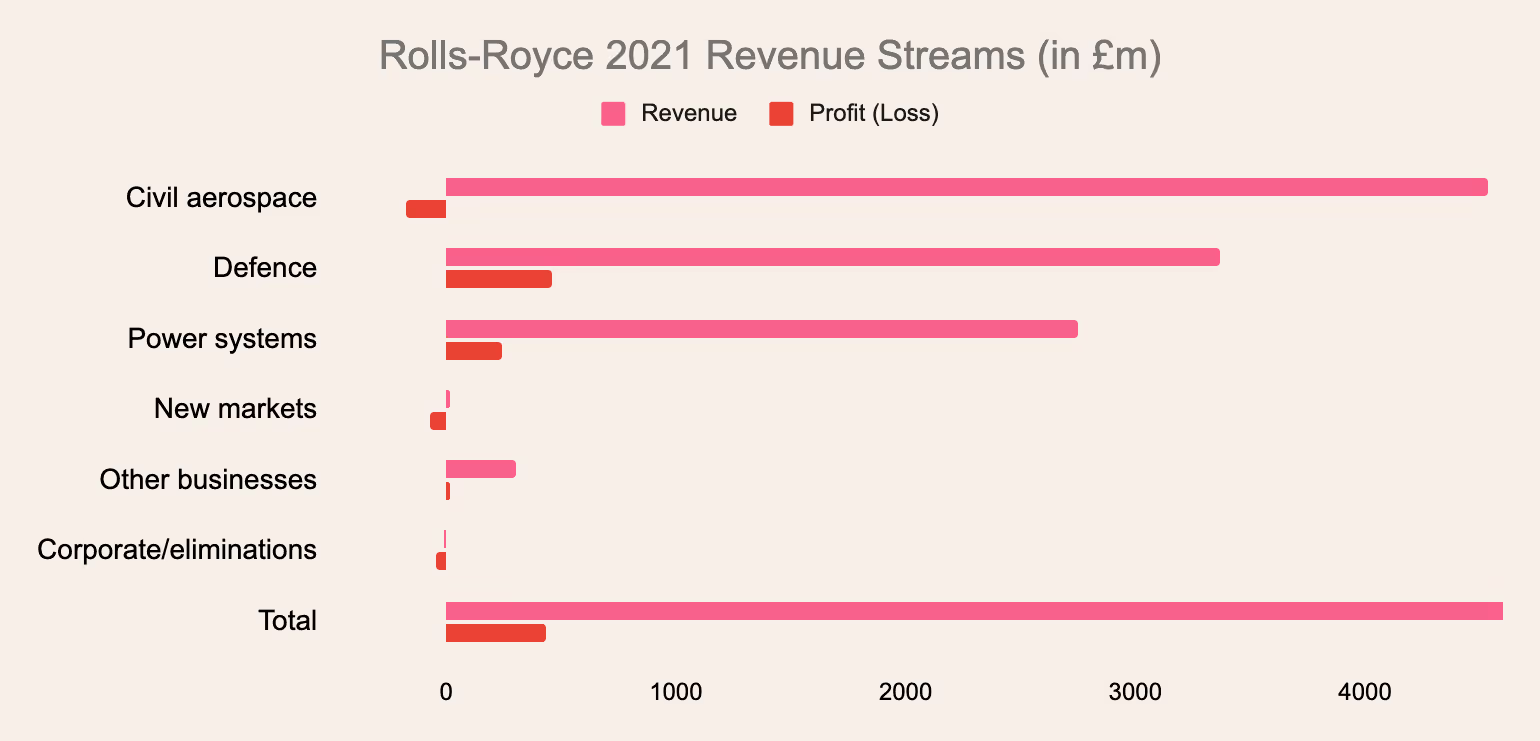

RR, as it’s traded on the London Stock Exchange (LSE), is an aerospace, defence and nuclear company.

While power systems including nuclear and electric propulsion energy are the least revenue generating of all its segments, they’re growing in importance.

Especially so in the UK. The firm recently announced plans to build a mini nuclear power station arm in Manchester and last year the government provided £210m to boost the nation’s power capacity.

Its share price has taken a beating in the wake of Covid, as demand for the firm’s large aircraft engines fell when the sector practically came to a halt. That means for now, Rolls-Royce’s main revenue segment relies on aviation getting back to business as usual.

So its share price is well below pre-pandemic levels. But if you believe the International Air Travel Association’s predictions that air travel will resume to 2019 levels by 2024, then its aeronautics division should eventually get a boost. The firm also estimates its SMRs will generate power by 2030.

That means it’ll be a while until its new plants are profit-making. But if the UK government keeps up with its nuclear investments, Rolls-Royce could be an important part of the transition.

5. Denison Mines

Denison Mines is a Canadian uranium miner. The firm has interests in several uranium projects like mills. Its Q1 revenue was $4.1m, a 24% increase on the year prior.

Some of its mills had to temporarily shut during the pandemic. Now that it’s able to kick things into gear again, it has benefited from a much higher rate of uranium mining.

Denison is also exploring several new sites, some of which are wholly owned, others are joint ventures. Because the company is mostly about exploration, and isn’t massively exposed to the results of the drilling and surveying, it’s somewhat sheltered from the risk of a project leading to unfavourable results.

Still, exploration is a costly venture. During its first quarter, eight exploration field programs cost it $2.3m, and there’s no guarantee any will turn up with Uranium. For now, there might not be a huge rush for Denison to uncover the goods. There’s still a large global supply of uranium, the big problem is that a lot is sitting in Russia.

Factors influencing a nuclear stock

That’s a key takeaway here: as reserve drawdowns continue, demand for uranium will eventually overpower what is currently available (or willing to be sourced). And when demand exceeds supply, uranium energy stocks could get a skip in their step.

If it does though, any share price boost for some uranium investments won’t be felt across the board. And it’s only the mines actually able to get capacity up with the potential to see their share prices go up too.

Say what you will about its tainted past, nuclear is the most affordable, low-carbon energy option we have. And with energy bills set to spike to £3,000 by January, the status quo clearly isn’t working. The question is whether nuclear will be a part of the answer, and if so, to what degree.

There’s no shame in waiting to see which companies are a part of that transition, if any.

Being overly reactive (pun intended) to headlines in the meantime is a much riskier play. And if there’s anything we can learn from reactors, it’s that a balanced risk assessment is always the best approach.

Build your financial knowledge and be in a better position to grow your wealth. We offer a wide range of financial content and guides to help you get the insight you need. For example, learn how to invest in stocks if you are a beginner, how to make the most of your savings with ISA rules or how much you need to save for retirement.

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)

%252520(1).avif)

.avif)

.avif)