Last month, back when we could go outside and buy stuff without queuing, we wrote about the sudden plunge in oil prices.

As you’ll know if you read that piece, oil prices fell in March as demand from China fell and OPEC+1, an organisation comprised of the major oil-producing countries, failed to reach an agreement that would have seen the member states reduce production and artificially boost prices.

All of this was followed up this week by crazy headlines declaring that companies were now paying people to take their oil, rather than selling it to them.

To be honest, this probably doesn’t even sound that weird to most people. COVID-19 has made the world a strange place. Long queues, face masks, lockdowns — it’s like there was a glitch in the Matrix and anything can happen.

Still, Morpheus hasn’t emerged just yet and there is a reason that the drop in oil prices is happening.

Why is the oil price falling?

In simple terms, low demand and high supply.

When we wrote about the drop in oil prices last month, there were really two causes for it.

The first was that large parts of China, which is the world’s biggest energy consumer, had gone into lockdown. Analysts have estimated that the country will use 20 per cent less oil in 2020 than it did in 2019.

The other factor was that the OPEC+1 countries did not make an agreement to cut oil production. Less oil would mean that the price of the commodity goes higher.

Since then, almost every country in the world has put some sort of lockdown in place. Even in countries where this hasn’t been done, like Sweden and Belarus, people are still consuming less energy.

As a result, the lower demand for oil, which was previously confined to China, has now spread across the entire world.

Like any tradeable asset, if the quantity of oil remains the same but demand for it goes down, then its price will drop too.

What’s happening now?

If you’ve been stuck at home, scrolling through an endless Twitter feed of news, then you may have seen journalists writing about how oil companies are actually paying people to get rid of their oil.

This is accurate but doesn’t capture the whole truth.

The key thing to understand is that oil prices are observed in futures contracts. A futures contract is an agreement to pay a certain price for an asset, like a barrel of oil, at a future date, known as the ‘expiry date’. Incidentally, Freetraders were discussing futures contracts on our community forum this week, so you can read more about them there if you’re interested.

This week, the price of NYMEX futures contracts in West Texas Intermediate (WTI) — a specific grade of crude oil — for delivery in May, dropped below zero for the first time in history. At its lowest point, the May contract was trading at -$40.32 per barrel. Trading in this contract expired on Tuesday. This meant that people were willing to pay someone to take their oil from them.

WTI is often quoted as a benchmark figure for oil prices by people in the financial markets. But it’s worth noting that the negative WTI prices quoted in the media were only for May futures contracts, not for June and other future dates. And though those later contracts are falling in value too, they haven’t dropped into negative territory yet.

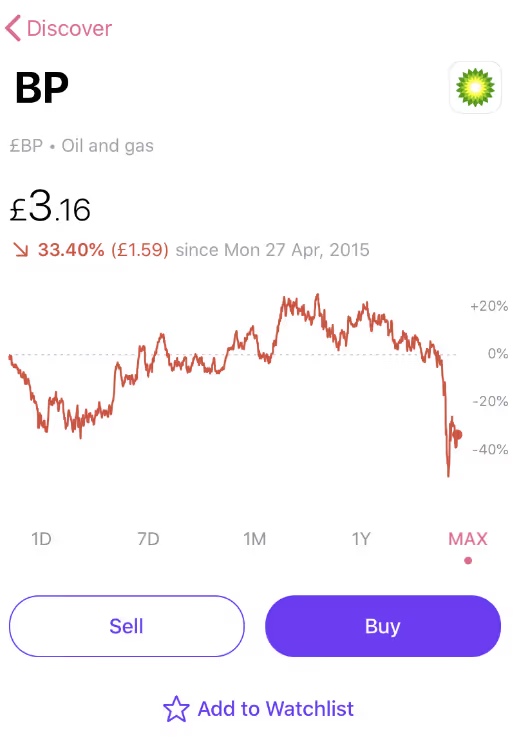

The WTI is also just one benchmark figure for the US. Brent Oil, for example, is another benchmark figure for oil produced in the North Sea. Though it lost about 40 per cent of its value this week, May futures contracts were trading at lows of approximately $16 per barrel but not negative numbers.

Why did oil drop into negative rates?

As we’ve already seen, coronavirus is causing demand for oil to drop dramatically. This has pushed the price of oil down.

But the other problem is that, because oil is not being consumed, there is a surplus which has to be stored somewhere.

In the US, there is now so much excess oil that companies are struggling to find places that they can keep it.

That problem then transfers on to people trading in futures contracts. Holding a futures contract in oil means that you will be buying a bunch of the commodity at a certain point in the future, unless you sell it before the expiry date. A lot of traders have no intention of holding the contract at expiry and if you have nowhere to store that oil, you’ll probably want to get out of that contract as fast as possible.

This is ultimately what happened. So many people were trying to get out of their May contracts, but no one was looking to buy so they ended up having to pay people to take them off their hands.

What’s going to happen?

Though it now seems like a distant memory, OPEC actually reached an agreement to cut oil production less than two weeks ago.

We are yet to see if that will have any impact given that any cuts will have to also take into account the huge drop in global demand for oil.

But as you can tell, the world is in a fragile, volatile state.

As we write this, Donald Trump has just threatened to blow up any Iranian boats that harass or attack US ships. I mean, why not? We could use some more chaos at the moment, right?

Anyway, this sent the price of oil up again as uncertainty around the ability of firms to transport oil increased.

All in all, no one can say with certainty what is going to happen. We’re just annoyed that the one time we can buy petrol for under a pound, we’re all in lockdown…

We’ve created one of the UK’s leading stock trading apps to help everyone build their wealth over the long term. Join over 1 million users that have chosen Freetrade for their general investment account, investment ISA or personal pension.

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)