Scrolling through a company’s adjusted accounts provides a great opportunity to acquaint yourself with the wonders of accounting wizardry.

Take taxi app Lyft’s latest quarterly results. According to regulatory-mandated reporting standards the firm lost $251.9m. But using adjusted earnings metrics it made a $23.8m profit.

How did Lyft account for this $275.7m discrepancy? The answer, as with so many tech-y companies today, is stock options.

What are stock options?

Those two words tend to conjure up images of Silicon Valley largesse or Leonardo di Caprio yelling down a phone on Wall Street.

The reality is a little more banal. A stock option is a contract that gives an employee the right to buy shares in the company they work for at a set price.

For instance, shares in a company may be trading on the stock market at £20. If you have an option to buy them at £10 then you might choose to do that. By buying the shares for £10, you could then sell them on for £20 and make a £10 profit.

Read more

Why did Palantir shares fall today?

CIA-funded Palantir goes public

Uber's meter is running high

Unlike options that trade on public markets, where investors buy or sell from other shareholders, shares in employee stock option programmes tend to be newly issued.

So a company will ‘create’ a set number of new shares and hand them to the employee in return for whatever price their option contract has set.

They do this, in part, to keep employees tied to a company and doing a good job. If you know a chunk of your pay is in shares, and those shares will be worth more if the company does well, then theoretically you’ll want to work harder and make the business succeed.

It’s also a way for early-stage businesses to attract talent that, because they tend to not have a lot of cash, they may not otherwise be able to afford. New shares can be created with minimal cash expense to a business, so they can preserve the cash they have and still offer an attractive package to prospective employees.

Stock option dilution

The most obvious problem with this is it increases the total number of shares in a company, meaning their value is diluted in proportion to how many shares have been issued.

As a simple example of this, imagine a company with 100 shares outstanding.

A stock option programme results in 100 new shares being issued. There are now 200 shares outstanding, meaning the original 100 now only entitle the owners to a 50% stake in the business.

A real life example of this can be seen with Palantir, which has unexercised options equal to approximately 27.5% of the company’s current free float.

It’s likely that not all of those will be exercised but it still gives you some idea as to how stock options can impact you as a shareholder.

To expense or not to expense?

Dilution is a big problem but the more controversial question is whether stock options granted to employees should be treated as an expense or not.

Like Lyft, if you scan through Palantir’s last quarterly report you can see the regulatory required financial statements show the firm lost $146m

Their adjusted earnings make things look much rosier as the firm made a profit of $116m.

The reason for this discrepancy is regulations require firms to treat options as an expense, as they would a salary. So if the options are worth $100m that will result in a $100m hit to a company’s bottom line.

Critics of this practice argue that, because no actual cash is paid out, it’s nonsensical to treat options as an expense.

But adherents disagree and point out that options are a form of salary with a meaningful value, so they should therefore be expensed accordingly. Doing so also means analysts can get an idea of how stock options are impacting the firm.

Stock options can mask losses

Wading into the no man's land between these two sides means you’re liable to have lots of abuse lobbed at you. And yet, for our dear readers, we’re happy to take the plunge.

It’s true that options usually don’t cost a company much in the way of cash and so it’s interesting to see how they’d perform when their effect is removed from the income statement.

The problem is options can’t be used in lieu of cash salaries ad finitum, even if adjusting them out implies otherwise. If a company were to try and do so then dilution would get worse and worse, continually depreciating shareholder value.

The company could choose to stop paying them to counter this but, if they didn’t have the cash to replace those options, then presumably they’d end up posting losses or be unable to pay a large chunk of their employees and make even less money than before.

That means a company which can only maintain profitability by adjusting out the effect of stock options is in an unsustainable position. It can’t keep using options instead of cash forever but if not doing so means it won’t be able to pay employees properly then it’s also going to flop.

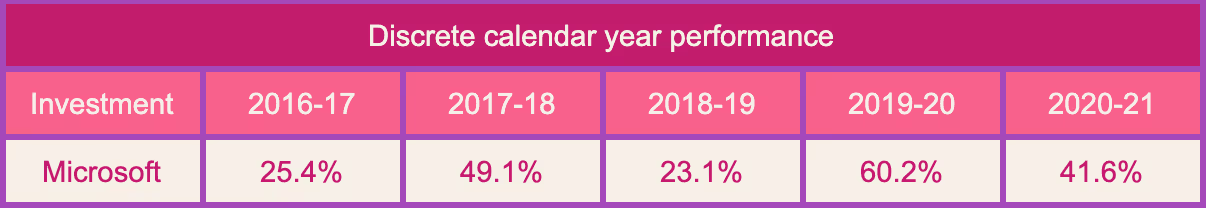

This is not to say stock options are always a bad thing. For instance, from 1995 to 2001, Microsoft handed out about 1bn shares through employee stock option programmes.

During that time its shares increased in value by more than 400% and, even if you’d included the stock options as an expense, the firm would’ve been profitable every year. That meant the share price appreciation far outweighed the dilutive effect that stock options had.

Firms which don’t see any uplift in shareholder value from stock options and which can’t turn a profit without adjusting them out of their accounts are a different story.

It’s fair for early stage companies to use stock options to keep and attract talent. But if there are no signs the business is becoming more cash generative, so that it can be profitable without paying stock options, that should be a big warning sign.

Silicon Valley executives may not want them on their income statements but stock options do have value, otherwise no one would accept them instead of money. Whether or not they should be on the statement is probably going to be an ongoing debate. But whichever side of that discussion you fall on, ignoring their impact entirely is a serious mistake.

What's your take on stock options? Let us know in the community forum:

Learn how to make better investment decisions with our collection of guides. They explain in simple language how to start investing if you are a beginner, how to buy and sell shares and how dividends work. We’ve covered investment accounts too, and how an ISA or a SIPP could be good places to grow your investments over the long term. Download our iOS trading app or if you’re an Android user, download our Android trading app to get started investing.

When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.If you are unsure whether a product is right for you, you should contact a qualified financial advisor.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)