Just like talk of Santa rallies and investors selling in May and going away, there’s a new-year aphorism in investing, ‘As goes January, so goes the year.’

It describes the tendency for the performance of the index in January to predict whether the rest of the year will be positive or negative come the Hootenanny.

In the UK, the rule held up last year but such was the magnitude of what came in between, it seems laughable to draw any type of conclusion around investor habits from it all.

In truth, it doesn’t really matter whether the saying holds true or not.

We all have the opportunity to change the course of our investments throughout the year, so we don’t need to leave it to a pithy market proverb.

The known knowns

While 2020 managed to throw most of us off-kilter by March, there were some hurdles we ultimately knew we’d have to navigate. And a reddit-fuelled short squeeze wasn’t one of them.

The coronavirus added to concerns over Brexit negotiations and the looming US election, as well as longer-term sagas like the path for record low interest rates.

As the GameStop story has shown, there will surely be a few newsflashes to shake us this time round too.

The trick is to control the controllables and set ourselves up as best we can for everything else by being well-diversified.

Globally, we aren’t out of the woods in terms of the virus, and the true economic cost hasn’t been felt yet.

But the thing investors hate most is uncertainty. And in this regard we start 2021 on the front foot.

The Brexit leaving drinks came and went, vaccines have been developed and are making their way round the world, a new president has been installed and a generous US stimulus package looks set to land in Americans’ bank accounts.

There are still big near-term hurdles including the tail-end of all of the above, the sustainability of the US tech run and, the global rebuilding of jobs and post-corona economies.

But we should give ourselves a second to take stock of the journey so far, before we look at whatever comes next.

If this week’s meme stock antics have told us anything, it’s that whatever does come next will be predictably unpredictable.

Each country and sector will come out of the current malaise at their own magnitude and direction, with their own obstacles and tailwinds.

Here are some of the themes, hurdles and opportunities in global equities investors should keep in mind during the year ahead.

- UK: a value hunting ground?

- US: tech valuations high

- Europe: a delayed recovery?

- Asia & emerging markets: China - first in, first out?

- Japan: growth hinges on recovery

UK: a value hunting ground?

A calendar year fall of 14.3% means the index of the UK's 100 biggest companies suffered its worst year since the financial crisis. Of course, that alone doesn’t mean 2021 will be any better.

But despite the UK stock markets negative start to this year (the UK 100 index finished down marginally in January) there’s a bit of optimism building in the background.

Whether it’s because we expected the world to have fallen apart by now, or a down-to-the-wire Brexit divorce had our nerves shot, we seem to be feeling something close to relief.

For investors, this disconnect between broad optimism and a low base to start from means the UK market now looks incredibly cheap.

Cheaper, in fact, than its global peers for at least 25 years and undervalued by as much as 31% according to Credit Suisse.

Valuations are low but the obvious reasons for them have largely passed.

And while the economic fallout of the virus is a concern, the prospect of actually making it out the other end hasn’t lifted the UK market back to its pre-pandemic levels just yet.

Compare the UK 100 to the S&P 500 and the result is a rather stereotypical vision of a slightly repressed starched-collar wearer against an altogether cheerier and rosy-cheeked go-getter.

The question then, is if the UK is out of favour for another reason.

Everything’s bigger in America

The lack of in-vogue tech has been a big stumbling block in the index’s performance since March lows.

The UK stock market is still dominated by stalwart pharma companies, banks and legacy tech like Vodafone. Pitch them against the US leaders and the UK starts to look a bit backward.

That’s made the index’s turnaround quite bland in comparison but what happens if the bottom falls out of the Nasdaq stars?

Top end sector valuations are dizzying and, while a dearth of the likes of Tesla and Amazon last year held the UK back, an alternative to toppy tech in 2021 might become attractive.

In that sense, the UK could well be too cheap to ignore.

Smaller companies which tend to have a greater emphasis on serving the domestic economy could do well when we’re allowed back out en masse.

An illustrative example might be escape room-operator Escape Hunt. With a business built on in-person experiences, it has done well to shift customers online in the interim and raise money to keep the lights on and even expand.

If firms like this in the service sector can hold on, a reopened economy could release the nation’s pent-up spending power.

The UK savings ratio hit a record 29.1% after the first lockdowns so we do have the money, we just need to have the chance to get out and spend it.

There are other sectors which haven’t quite captured the positive mood like their US peers. Housebuilders, consumer electronics and auto sales could benefit from a look beyond tech, and their high valuations.

Newer investors won’t be used to hunting for value but it might just be the year they get to learn.

There will be challenges to an economic recovery coming soon though. Unemployment has risen to 5.0% and could spike if the Chancellor doesn’t ease the pressure likely to be brought on by the end of furlough in April.

The danger is that zombie jobs, only able to exist currently because of furlough, will suddenly become untenable for many employers.

And the housing market will also be a near-term focal point. The Help to Buy scheme will be limited to first-time buyers before being phased out in 2023, and the Chancellor’s stamp duty holiday will come to an end in April.

Housing managed to hold up well in 2020 but a large part of the demand will have been driven by buyers aiming to capitalise on both of these advantages before they end.

US: tech valuations high

Where the UK stock market had Brexit front of mind during the latter part of 2020, the S&P 500 had the US election. The final line under the contest may have been drawn only recently but the new administration is now getting its feet under the table.

For investors, actually having Joe Biden in the oval office takes one less uncertainty out of the equation.

Even if they aren’t supporters, sometimes even your least favourite result is better than extended indecision.

Joe Biden’s arrival comes with clear pro-green energy messaging, not least in early moves to cancel the controversial Keystone XL pipeline. This could be where investors see the opportunity over the next year, as the incoming president makes his sustainable intentions clear.

But the main focus will be on the US tech run, and whether it has the legs to continue in 2021.

The most crowded trade for most of the year left the sector sitting at 26x forward earnings estimates in December. Individual valuations like Tesla’s are sky high and, according to Refinitiv, earnings are projected to grow by around 14% next year, slower than the 23.2% expected for the broader S&P 500.

There’s also the threat of regulation. The sector has so far managed to avoid calls to dismantle what have become the biggest companies in the world. But how the leaders evolve from here will be under scrutiny from US and European regulators.

If there is a correction it will likely have something to do with tech, if even just to normalise stretched valuations. But, with Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook and Tesla collectively making up over 20% of the value of the S&P 500, its effects could ripple outward significantly.

The pandemic has also allowed big names in other sectors to extend their lead.

While companies with precarious balance sheets, slim cash reserves and limited tech foresight have struggled, the ship-shape business have been less affected.

Firms emerging from the pandemic with a well-capitalised business have more than a fighting chance of seeing off low quality competitors and gaining market share.

Unfortunately, it won’t be about quality for smaller firms who may simply not be able to last the distance.

Bill Ackman, head of Pershing Square Holdings, uses Starbucks as an example here.

With many small-time coffee shops unable to survive the pandemic, and Chinese competitor Luckin entangled in a case of accounting fraud, the competitive landscape will be very different when the economy opens back up fully.

This could pave the way for a boom in corporate consolidation in 2021. If the gap between the leaders and everyone else opens up and well-capitalised companies can increase their moat by buying up the competition cheaply, we could be in for a bumper year in mergers and acquisitions.

On a personal-spending level, the savings built up among US consumers could be unleashed across the travel and service sectors.

We’ve already seen North American buying habits prop up the likes of Guinness-owner Diageo and tonic disruptor Fever-Tree with their lockdown spending.

And the more these shoppers are saving, the more they will feel justified in considering premium purchases that would normally break the bank.

This could extend beyond drinks into luxury goods but is heavily dependent on the trajectory of the economy and stimulus measures early in Biden’s presidency.

Europe: a delayed recovery?

Hotspots like Italy and Spain were some of the first regions outside of China to be affected by the virus spread last year.

Other countries like the US and Brazil have experienced steeper growth since then but, as a continent, Europe still sits above the rest in terms of total virus cases.

Wider policy-makers and individual states responded quickly, aiming to manage the situation on a local level as well as across the continent.

In March The European Central Bank (ECB) launched its €750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) to support the economic fallout from the coronavirus spread.

With increases in June and December, the total purse now stands at €1.85 trillion with the intention to continue net asset purchases until the virus crisis is over and until at least March 2022.

But while interest rates will remain low and economic aid is coming to member states in the form of the EU Recovery Fund, it is still the health emergency that threatens to derail Europe’s return to normal in 2021.

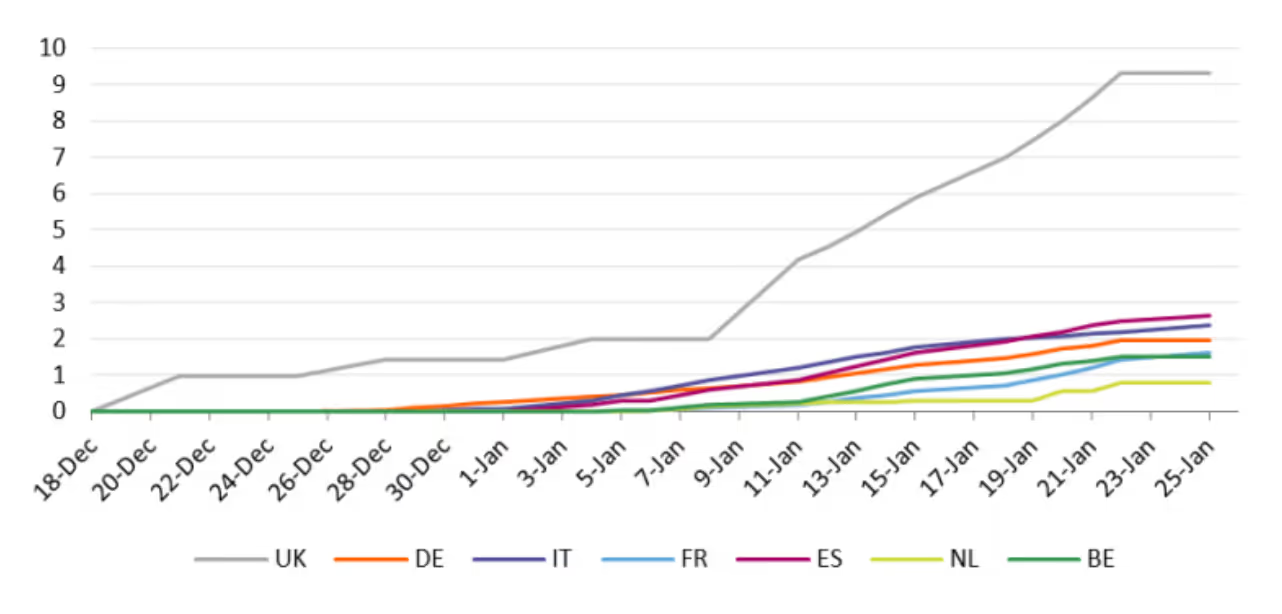

Around 11% of the UK population has received a vaccine by now but that figure drops to less than 2% in many eurozone countries.

Recent updates from both Pfizer and Astrazeneca have included mentions of fewer vaccines being delivered to the continent than had been planned - down by 60% in the latter’s case.

A lower and slower inoculation rate suggests Europe’s emergence from lockdowns and curfews will be delayed, perhaps into the second quarter and beyond.

There is a clear knock-on effect for the tourism-heavy southern European economy, especially heading into the summer months.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) predicts passenger traffic this year will be less than 50% of the volumes seen in 2019 and won’t get back to previous levels until 2024.

Airlines, accommodation, leisure activity, hospitality - the sectors that investors have been eyeing for value will have to wait until restrictions are lifted in order to regain any type of market attention.

The speed and magnitude of Europe’s vaccine rollouts will therefore be intrinsic to its ability to get its major economic drivers back on track.

More positively, German industrial sentiment is on the rise.

The mood among exporters hit its highest level since October thanks to clarity on Brexit, and the German economy apparently avoiding recession.

Europe is unlikely to be a region in which investors take a high conviction stake, given its hurdles. However, supportive monetary policy, efficient deployment of the Recovery Fund and economies springing back to life could provide an environment for shares to flourish.

Asia & emerging markets: China - first in, first out?

Starting this year with another round of regional lockdowns in China is a timely reminder that the country isn’t rid of the virus just yet.

Despite stringent measures taken to curb the spread, health authorities in the country identified a spike in cases in Hebei province, which borders Beijing, resulting in lockdowns affecting more than 11m people in the city of Shijiazhuang.

Next month’s Lunar New Year holiday is clearly on the government’s mind - a time when families travel to meet, and the occasion that reportedly facilitated a rise in Covid-19 cases last year.

From China being the focus initially, most of the latter part of 2020 was spent keeping up to date with the western world’s response to stopping the spread.

In part, that’s because in the summer investors were starting to see evidence of China being first in and first out of the crisis.

The regime’s ability to impose strict social shutdown measures and the cultural memory of the SARS outbreak both seemingly heightening a swift response to the spread.

And while that wasn’t the end of the story by any means, investors began to look to China as a kind of predictor of what might happen to western economies who were further behind in the saga’s chronology.

On the whole, stricter management of the spread so far, and seemingly stricter controls going forward, suggest the country is well-placed to deal with further waves, even if it can’t prevent them.

And the market has broadly indicated its acceptance of this. Shares in Chinese companies dropped less en masse and recovered quicker than their global counterparts over the course of the year.

The consumption transition

One of the most important aims for the Chinese government throughout all of this is keeping the country’s consumer story intact.

The country has long been evolving from being the world’s toy factory to an economy of domestic consumption, with authorities working hard to avoid the middle income trap.

China’s rising middle class increasingly has the cash to spend and domestic companies have been encouraged by the government to serve them.

Coronavirus threatens to derail this, as consumers the world over have been physically restricted from in-person spending even if they have the money to do so.

The fall in the share of private consumption in China’s gross domestic product in the first half of 2020 was enough to undo five years of the transition’s progress.

Given China’s plans, it has more on the line than most economies.

But the situation has also granted one of the world’s most tech-savvy nations the opportunity to speed up the next obvious step to consumption: offline to online.

Online retail sales rose from 21% to 25% in the first half of 2020, with the online gaming sector growing revenues by over 22% in the same period, according to Société Générale.

Shares in the likes of TAL education, New Oriental and 51Talk have benefited this year, as they have been able to offer a suitable online alternative to in-person teaching.

Crucially, 2021 will shed light on whether that transition is deemed sustainable or families are just looking for a means to an end for now.

China’s hold on commodities

Vast industrial and infrastructure projects have meant China has swallowed up the global supply of oil and metals used in production processes, like copper.

The hike in price of iron ore, which provides the steel these structures need, is a direct result of the country’s economic growth.

And even with its programme to transition into a consumer-led society, it isn’t done with the public projects just yet.

In fact, with retail taking a dive due to lockdowns in 2020, the industrial side of the economy has been keeping the ship steady.

If the retail malaise continues and infrastructure shoulders even more of the country’s growth ambitions, its commodity usage will become even more important.

India: China 2.0?

China isn’t the only rapidly changing nation in Asia.

In terms of capitalising on demographic changes like the growth of the middle class, India has long attracted investors too.

With a population of 1.4bn making up 18% of the global total and an average age of 28, there could be a wealth of growth to tap into.

From a top-down perspective, India’s workforce sits behind only China in sheer numbers.

If it moves into top spot through adding another 200m people by 2050, as the current growth rate suggests, we could see an even bigger boom than we have seen this far in China.

But while better education, increased urbanisation and the eventual rise in consumption are positive trends that show no sign of stopping, the country’s stock market has not been immune to last year’s setbacks.

Close living quarters in cities and a significant portion of the population with little access to structured healthcare meant India was hit harder than a lot of its neighbours.

But, just as we have seen in the west, 2020 has sped up changes that were already in motion.

With China’s reduced reliance on manufacturing, global corporations have been looking at moving to the likes of Vietnam and India for some time.

Given India’s abundant workforce and growing middle class, firms like Apple have made plans to manufacture products in the country for export and domestic buyers too.

Despite prime minister Narendra Modi’s ‘Make in India’ initiative, designed to unlock the country’s potential, the country still needs a push to really drive its manufacturing sector.

Firms moving production away from China could be that catalyst.

The country’s recovery is paramount though. How it manages inoculating a vast population and stemming further spreads will be the first indication of how this long-term demographic is boosted or derailed.

Investors should remember that emerging markets carry risks like these that more developed nations have come through. But sometimes that carries opportunity too.

Japan: growth hinges on recovery

Finally, Japanese shares started to see a bit of positive momentum at the end of 2020.

MSCI Japan’s pullback on renewed virus and lockdown fears have halted that progress so far this year but contained in that vignette is a sign of what sustained good news could provide for investors.

A pick-up in earnings could bring investors back to Japan’s exporter-heavy economy, especially if global growth hits its predicted level of around 6%.

Forecasts put Japanese earnings 60% above 2020 levels this year, with another 9% coming in 2022. If investors rotate away from the pricey tech elsewhere in search of value, Japan could offer a home to gains made elsewhere.

Given that corporate earnings in Japan are expected to flourish next year, as part of a global rebound, the market’s current low valuation levels could be attractive.

Manufacturing is a core sector in the country and, while the car segment has restarted slowly, the likes of tech products and electronics have shown an uptick as the demand for goods outstrips out-of-home services amid lockdowns.

If this continues and demand benefits from eventual pent-up consumer earnings ending up in bigger TVs or better sound systems, the momentum of the end of 2020 could resume.

The new government has also stated its ambitions to ramp up a digital transformation of the country’s public sector and head towards total carbon neutrality by 2050.

This opens the way for investors interested in environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards to look again at Japanese equities. If companies are being encouraged to reduce their effect on the environment, it could usher in a more competitive and sustainable landscape over heavy polluters elsewhere in investors’ portfolios.

Freetrade is on a mission to get everyone investing. Whether you’re just starting out or an experienced investor, you can buy and sell thousands of UK and US stocks, ETFs and investment trusts commission-free on our trading app. Download the Freetrade app today and join over 850,000 retail investors.

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

-min.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)