We’re talking bonds this week. Why not try out our gilt calculator?

In 1624, in the Low Countries, on a strip of vellum a simple agreement was recorded. It saw 1,200 guilders lent to a water board to maintain river dykes. The bond promised 2.5% interest forever. It was bought by Elsken Jorisdochter, a widow.

The document has witnessed almost four centuries of history, sitting in ledgers as the Dutch Republic fought wars of religion and empire. Under Napoleonic rule in 1810 the Dutch state imposed the Tiercering, a major restructuring that cut interest payments on many perpetual bonds to just one-third of the original rate. The 1624 bond’s 2.5% annual coupon was cut to roughly 0.83%. And for long stretches of the 19th century, no interest was paid, or only partial payments were made.

But our perpetual bond, or perp, was still there when Waterloo redrew Europe, when railways began to unfurl across the continent, and when the guilder became the euro.

In the twentieth century, as Europe bore witness to a couple of minor skirmishes, its coupons were noted, then scribbled into addenda once the vellum ran out of room.

Today, officials in Utrecht still honour its interest. What began as a local instrument for flood control has become a document that has outlasted empires, defaults, and ideologies.

Going Dutch

The Dutch Republic, much of it reclaimed land, depended on an elaborate system of dykes and canals to survive. Local water boards with tax-raising powers leant on citizens to keep the rivers in check. In exchange, they offered a perpetual promise of interest.

These financial instruments established the idea that institutions could issue obligations lasting beyond a single human lifetime. The water boards outlived their original lenders, their monarchs, and in many cases their national governments.

The Dutch Golden Age was built on this financial ingenuity. Bonds like the one purchased by Elsken Jorisdochter financed flood protection and infrastructure, but the same techniques later scaled to canals, trading companies, and sovereign debt. They allowed a small republic to punch well above its weight in global trade and empire-building.

Perpetual motion

In 1648, the same year the Treaty of Westphalia ended the Thirty Years’ War, the Dutch water board of Lekdijk Bovendams issued another perpetual bond. Written on goatskin, it promised a 5% annual coupon to finance flood defences.

Today it belongs to Yale University, which acquired it in 2003. The bond is still honoured, and in 2015 Yale collected twelve years of interest arrears. A modest €136.20. After the original parchment ran out of space clerks attached a paper addendum to continue recording payments. As a bearer instrument the obligation can be claimed by whoever presents it.

In September 2024, Euronext Amsterdam held an event to honour interest payments on two other perpetuals from the same lineage, one from 1638 and one from 1765. The bonds were issued by the same Dutch water authority and still yield 2.5% hundreds of years later.

Debitum Britanniae

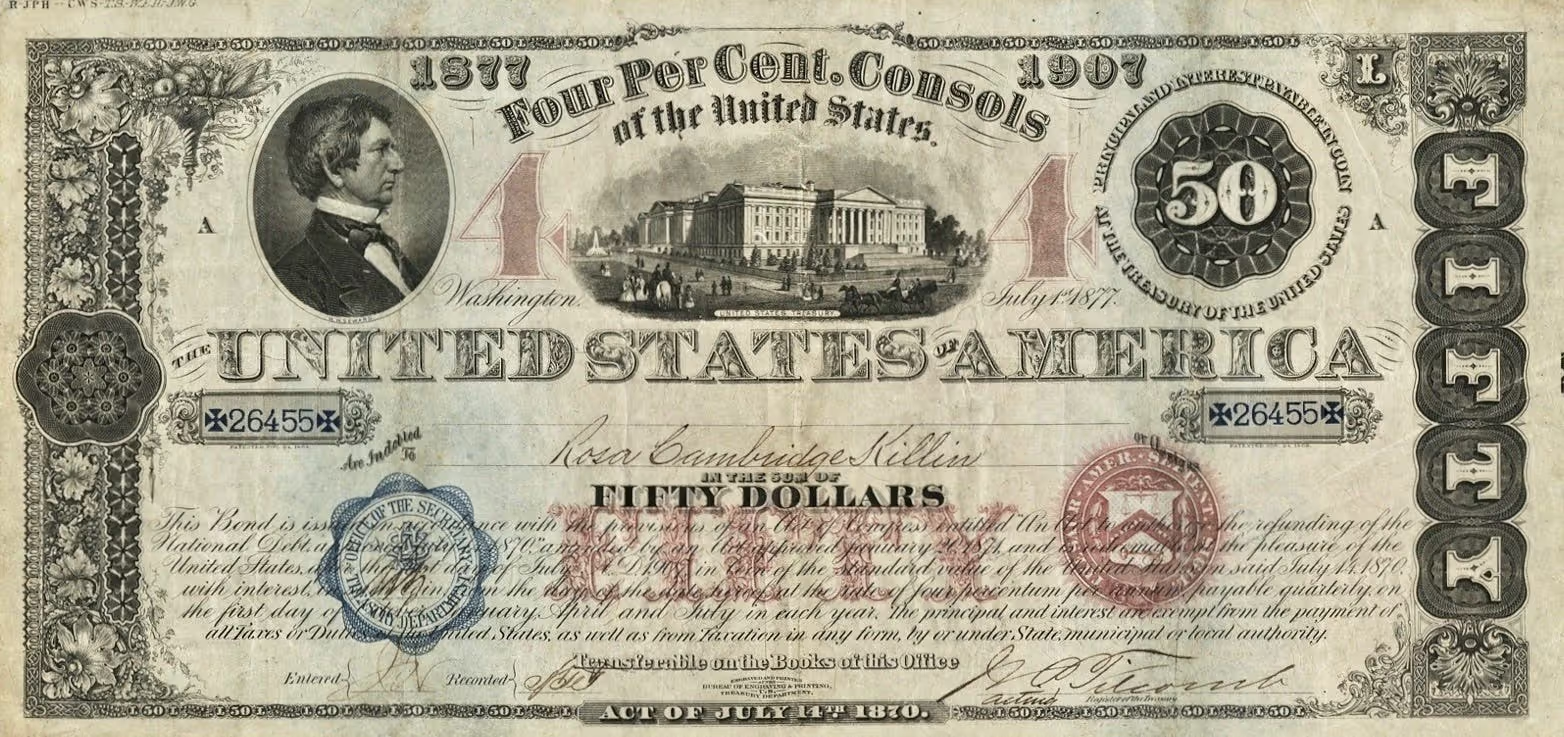

In 1751, the British government brought together a patchwork of debts into a single perpetual issue. These consolidated annuities were known as consols. They paid a fixed coupon but had no maturity date, meaning the government could, in theory, keep them alive forever.

Consols funded wars against Napoleon, helped drive Britain’s 19th-century industrial boom, and were considered so reliable they appeared in novels and family estates as ‘safe income’. At their peak, consols made up half of Britain’s national debt. They were only fully redeemed in 2015, more than 250 years after their creation.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Russia issued bonds which were widely bought in Europe, especially France. These Russian imperial bonds financed railways, armies, and industrialisation. But after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, the new government annulled the tsar’s debts. The bonds became worthless overnight, leaving millions of French holding the bag.

Give it back

In 2017, Austria issued a bond maturing in 2117. It was a gamble that investors would accept a 2.1% coupon as fair compensation for lending to a government for 100 years. At the time, yields across Europe were near zero so 2.1% looked good. The bond was oversubscribed and its price climbed as high as 155, delivering strong capital gains to early buyers.

But the long life of a bond makes it very sensitive to interest rates. When global rates surged in the new normal, post-pandemic 2020s the bond’s price cratered, falling below 60 by late 2022. Investors could now earn higher yields in 10- or 30-year bonds without taking on a century of duration risk. Today the bond trades with a yield closer to 2.8% – higher than its original coupon – reflecting the extra compensation investors demand to hold something so long-dated.

The volatility of long-term or perpetual bond prices points to one of the reasons that some of the most notable issuance are from niche, municipal borrowers. For nation states, they have rarely made sense as investor demand could waver significantly.

War bonds

The two world wars saw governments around the globe issue vast amounts of debt marketed to their own citizens. Households were urged, among other things, to buy bonds ‘for victory’. Some of these were designed as perpetual or ultra-long obligations, especially when governments could not predict how long the conflict would last.

But not all promises survived the test of time. The hyperinflation of Germany’s Weimar Republic effectively erased war bondholders’ investments following World War One. During the American Civil War, the Confederate States issued bonds to fund their war effort. Printed on ornate paper, some were backed by the value of cotton exports, an asset that became untradeable under Union blockade. When the Confederacy collapsed, the bonds became worthless. Today they are popular among collectors, often fetching hundreds of dollars at auction.

Scripophily

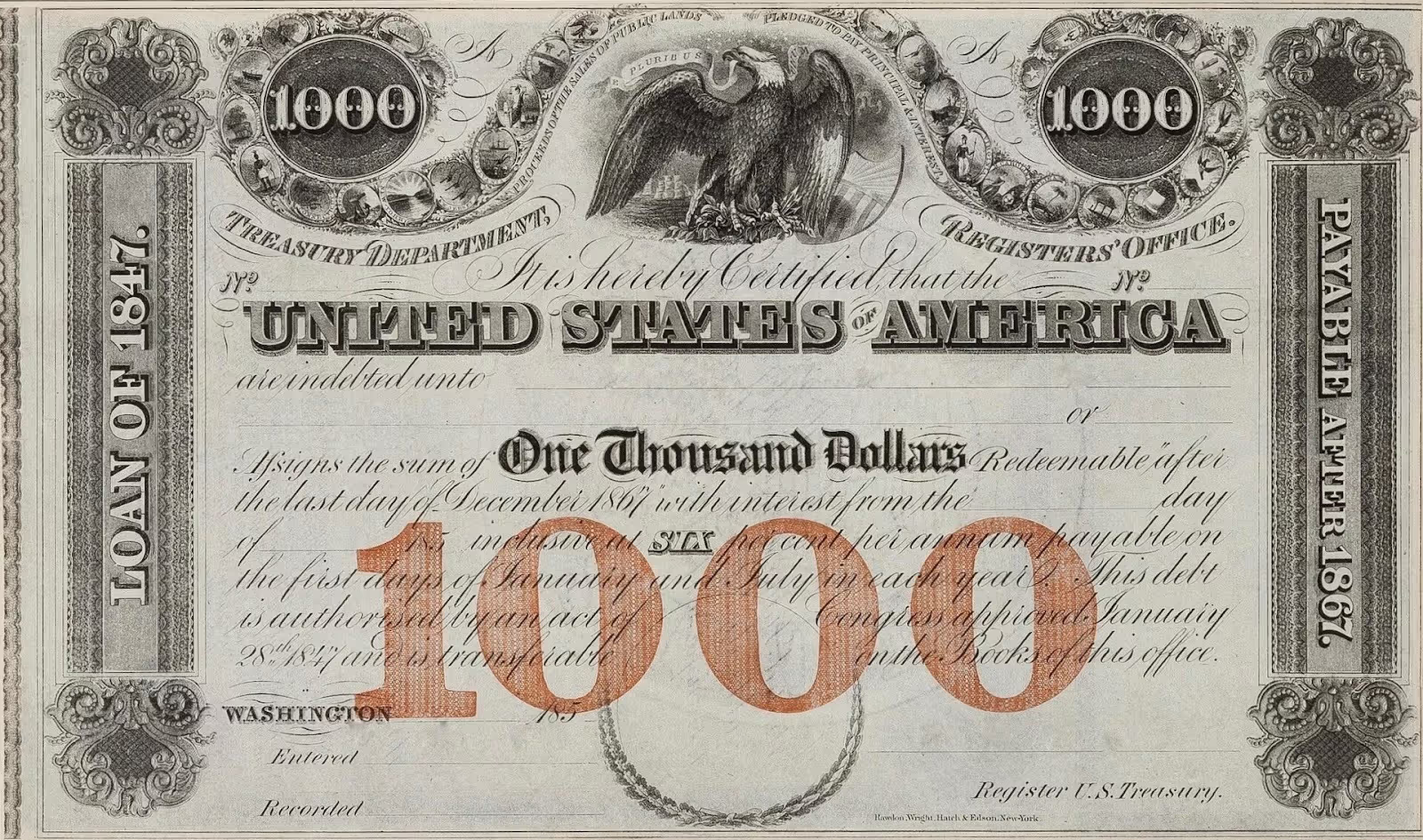

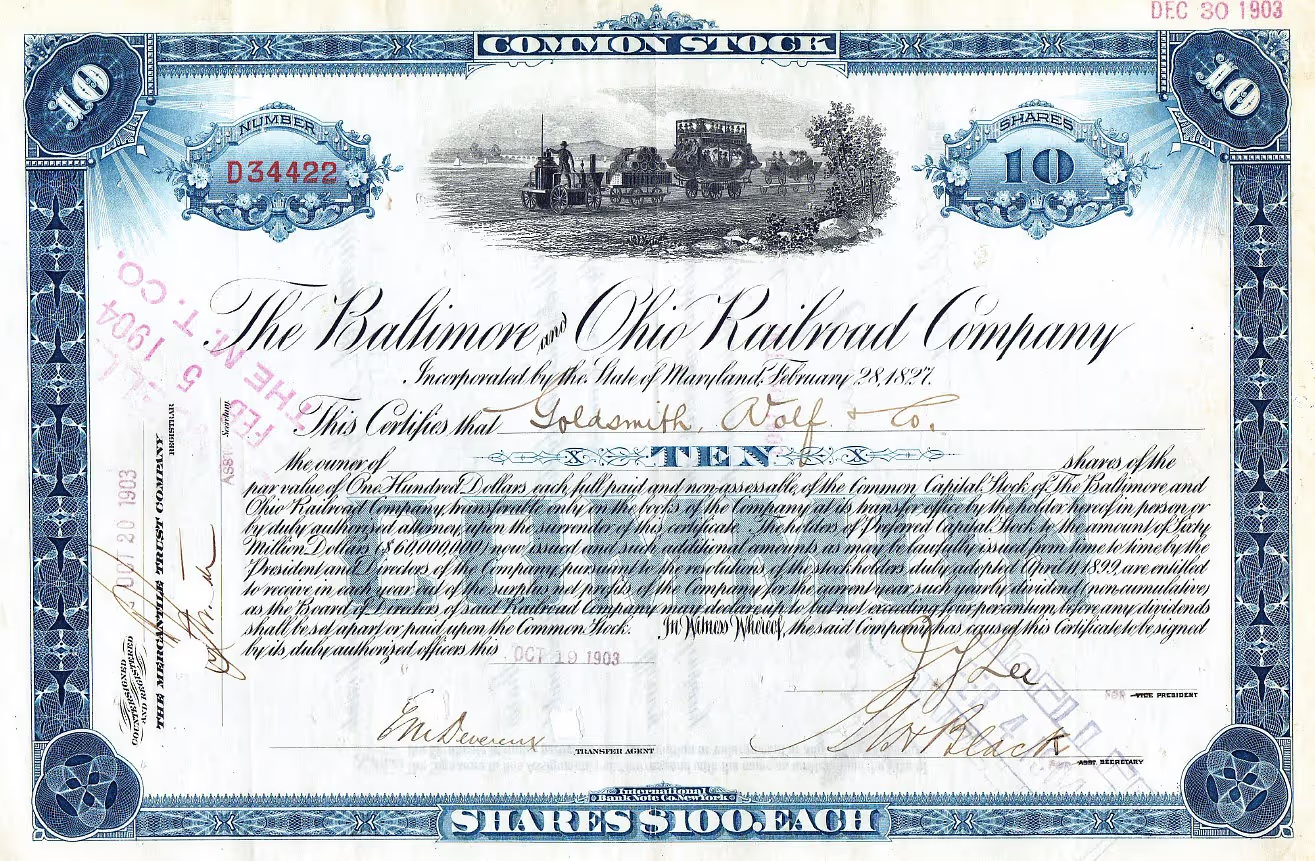

Scripophily – the study and collection of stock and bond certificates – has grown into a niche market. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, governments and corporations issued bonds with intricate engraved designs. Goddesses representing industry and commerce, steam locomotives forging ahead, or portraits of monarchs framed by baroque flourishes. The visual language was deliberate, designed to inspire confidence.

Today these pieces of paper survive as art and artefact. Confederate war bonds are prized for their calligraphy and symbolism. Russian imperial bonds, ditched by the Bolsheviks, are popular among French collectors whose aforementioned ancestors once held them as genuine investments. Old railroad and canal bonds circulate, sometimes fetching more than their original face value.

Worth the paper its printed on

Investors have always been drawn to the idea of a ‘forever income’. Who wouldn’t be? Perpetual bonds promise a scintilla of immortality in a world of grinding uncertainty. They appeal to dynasties and institutions that think in centuries rather than financial quarters. Universities, insurers, and churches historically favoured perpetual annuities as assets that could underpin endowments or charitable works.

Yet this edge can become a trap. Inflation steadily erodes fixed coupons. What seemed like a reliable stream of guilders or pounds or dollars in one century can become pocket change in the next. Yale’s collection of a few euros on its 17th-century bond is testament to that paradox. A historical curio, honoured faithfully, yet worth almost nothing in real terms.

This should not be read as personal investment advice and individual investors should make their own decisions or seek independent advice. This article has not been prepared in accordance with legal requirements designed to promote the independence of investment research and is considered a marketing communication.When you invest, your capital is at risk. The value of your portfolio can go down as well as up and you may get back less than you invest. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.Freetrade is a trading name of Freetrade Limited, which is a member firm of the London Stock Exchange and is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Registered in England and Wales (no. 09797821).

.avif)

.avif)

%2520(1).avif)